Realism Theory: A Clear, Practical Guide for Research and Writing

Realism in Plain Terms

- Realism is a theory about reality.

- It starts from the idea that the world is not “made up” by our opinions.

- Many things are true or false regardless of what we personally believe.

- Realism is also a theory about knowledge.

- It asks how we can know what is real.

- It assumes evidence and careful reasoning can move us closer to accurate understanding.

- Realism is a “reality-check” approach.

- It pushes against exaggerated claims, wishful thinking, and unsupported conclusions.

- It encourages researchers to focus on what can be justified with proof.

- Realism appears in many disciplines.

- In philosophy: it debates truth, existence, and knowledge.

- In science: it supports treating scientific explanations as describing real processes.

- In social science: it helps analyze institutions, power, and systems as real influences.

- In literature and art: it represents everyday life and social conditions faithfully.

- In international relations: it explains power, security, and state behavior.

What Realism Means in One Line

- Definition (simple):

- Realism is the view that reality exists independently of our beliefs, and knowledge aims to describe or explain that reality as accurately as possible.

- What this implies:

- Belief does not create reality (believing something does not make it true).

- Evidence matters (claims should be supported, not just asserted).

- Good research is accountable to the world, not only to interpretation.

- What realism is not:

- It is not “being negative” or “pessimistic.”

- It is not ignoring values or ethics.

- It is not claiming perfect certainty.

Why Realism Matters in Academic Thinking

- It anchors inquiry in evidence.

- It encourages observation, documentation, and verifiable support.

- It reduces the risk of writing “opinion essays” disguised as research.

- It supports explanation, not only description.

- It encourages you to ask “what causes this?” and “how does it happen?”

- It moves you from listing themes to explaining relationships.

- It helps handle complex real-world problems.

- Many outcomes are shaped by multiple interacting forces.

- Realism fits topics involving policy, systems, institutions, inequality, and constraints.

- It strengthens credibility and academic rigor.

- It supports clear reasoning, transparent methods, and defensible conclusions.

- It makes it easier to justify why your findings matter beyond your sample.

- It improves practical usefulness.

- Realism supports applied recommendations that match real conditions.

- It helps you avoid solutions that sound good but ignore constraints.

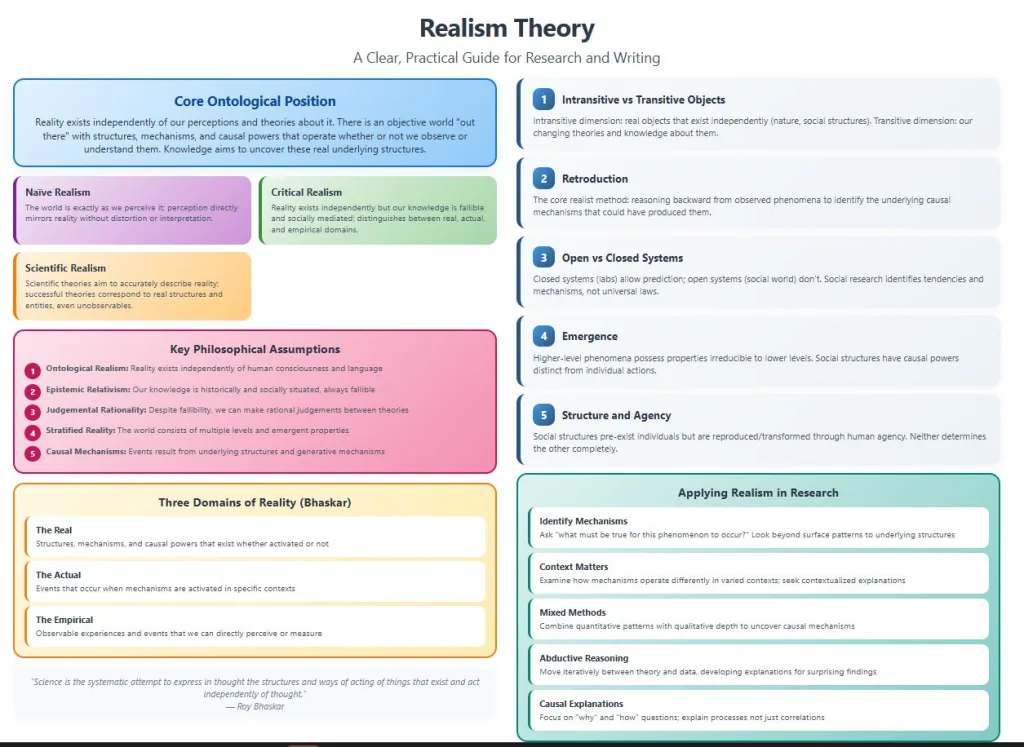

Core Assumptions of Realism

- Reality exists beyond the mind.

- Social and natural worlds have patterns and structures.

- These structures can shape outcomes even if people are not aware of them.

- Knowledge is possible, but imperfect.

- Realism accepts uncertainty and bias risks.

- It emphasizes improvement through better data, better methods, and replication.

- Truth is connected to evidence.

- Claims need support through data, logic, or credible sources.

- Stronger evidence increases confidence in conclusions.

- Explanations should connect causes and effects.

- Realism values causal accounts rather than only descriptions.

- It emphasizes mechanisms (how and why something leads to an outcome).

- Context matters.

- Realism expects outcomes to vary across settings.

- It examines how context shapes whether a mechanism “fires” or fails.

Key Concepts You Should Know

- Ontology (what exists).

- Realism assumes many things exist beyond what we think.

- In social research, it treats institutions, policies, and norms as real influences.

- It also accepts that social realities can be complex and layered.

- Epistemology (how we know).

- Realism supports evidence-based knowledge building.

- It accepts that researchers are human, so methods must reduce error and bias.

- It values transparency: show how you reached your conclusions.

- Causation and mechanisms.

- A mechanism is the “engine” that produces an outcome.

- Example: “fear of punishment” may be the mechanism behind compliance.

- Realism often asks: what process links cause and effect here?

- Objectivity vs. neutrality.

- Objectivity is the goal of reducing distortion.

- Neutrality is not always possible (values influence research choices).

- Realism emphasizes fairness, rigor, and evidence even when values exist.

- Levels of explanation.

- Individual level: beliefs, choices, skills, behavior.

- Institutional level: policies, rules, leadership, culture.

- Structural level: history, economy, inequality, power distribution.

- Realism often uses more than one level at once.

Major Types of Realism

Philosophical Realism

- Main idea:

- The world exists independently of our perceptions and language.

- Why it matters:

- It supports truth claims that are not reduced to opinion.

- It strengthens the idea that arguments must correspond to reality.

- Where it is used:

- Ethics, metaphysics, theory-building, debates about truth and meaning.

- Typical questions:

- What is truth?

- Do moral facts exist?

- Can we know reality or only interpretations?

Scientific Realism

- Main idea:

- Strong scientific theories often describe real entities and processes.

- Even if we cannot directly observe something, it can still be real.

- Why it matters:

- It justifies trusting well-tested explanations (with caution).

- It supports research that investigates hidden causes (genes, pathogens, systems).

- Common examples:

- Viruses, genes, gravity, and neurotransmitters are treated as real because evidence supports them.

- Typical research fit:

- Health sciences, biology, engineering, and other theory-driven empirical fields.

Critical Realism

- Main idea:

- Reality exists, but we access it through social life, language, and institutions.

- Social structures (class, policy, power) create real effects.

- What makes it “critical”:

- It investigates how power shapes outcomes and what gets treated as “truth.”

- It looks at deeper causes behind visible problems.

- Key focus:

- Context → mechanisms → outcomes.

- Structural influences and unequal impacts.

- Typical research fit:

- Education, public health, social work, organizational studies, policy evaluation.

Realism in Literature and Art

- Main idea:

- Ordinary life and social conditions are portrayed with believable detail.

- Core features:

- Everyday settings, realistic characters, plausible conflicts.

- Attention to social class, work, institutions, and social constraints.

- Why it matters academically:

- It can reveal social realities and historical conditions.

- It supports cultural analysis grounded in context rather than fantasy.

- Typical research fit:

- Humanities, cultural studies, media analysis, historical interpretation.

Political Realism (International Relations)

- Main idea:

- States prioritize survival, power, and security in a competitive system.

- Key assumptions:

- The international system lacks a single enforcing authority.

- Power and national interest strongly influence decisions.

- Focus areas:

- Alliances, deterrence, security dilemmas, conflict escalation.

- Typical research fit:

- Foreign policy, security studies, war and peace studies, geopolitics.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowWhat Realism Looks Like in Practice

- Treating institutions as real forces.

- Policies can shape choices and outcomes even if people dislike them.

- Organizations influence behavior through incentives and rules.

- Respecting constraints.

- Realism asks what limits action: money, staffing, laws, time, risk, political pressure.

- It avoids “ideal solutions” that ignore feasibility.

- Expecting patterns without oversimplifying.

- Realism looks for recurring trends while acknowledging exceptions.

- It expects partial regularities rather than perfect predictability.

- Welcoming mixed evidence.

- Quantitative: surveys, experiments, administrative data, statistics.

- Qualitative: interviews, focus groups, observations, documents.

- Realism supports triangulation when it strengthens explanation.

- Asking “what is really going on?”

- It checks surface claims against deeper drivers and context.

- It tests whether a popular explanation fits the evidence.

Realism Compared With Other Approaches

- Realism vs. Idealism

- Idealism emphasizes values and what “should be.”

- Realism emphasizes constraints, incentives, and what “is.”

- In research, realism helps test whether ideals can work in real settings.

- Realism vs. Constructivism

- Constructivism emphasizes how meaning and identity are socially built.

- Realism emphasizes that material conditions and structures still shape outcomes.

- Many studies combine insights, but realism keeps the focus on real effects.

- Realism vs. Positivism

- Positivism may prioritize only what is measurable.

- Realism accepts measurement but also studies deeper causal mechanisms.

- Realism is comfortable with “unobservables” if evidence supports them.

- Realism vs. Interpretivism

- Interpretivism prioritizes meaning, experience, and context.

- Realism includes meaning, but also investigates structural causes and constraints.

- Realism asks how systems produce the experiences people report.

Strengths of Realism

- Strong explanatory power.

- It links outcomes to causes, not only correlations.

- It supports mechanism-based explanations.

- High practical relevance.

- It produces recommendations that fit real-world constraints.

- It suits policy, health, education, and organizational problems.

- Strong fit for complex social issues.

- It accommodates context, inequality, and institutional influence.

- It supports multi-level analysis.

- Encourages responsible, defensible claims.

- It demands evidence and transparency.

- It reduces exaggerated conclusions that data cannot support.

- Supports transferability.

- By explaining mechanisms, findings can inform similar contexts.

- It clarifies what conditions are needed for outcomes to repeat.

Common Critiques of Realism

- It may oversimplify human meaning.

- Critics say it can underplay identity, emotions, and lived experience.

- Response: include qualitative evidence and interpret meaning carefully.

- Debates about “social reality.”

- Social facts (money, status, norms) can be real yet socially constructed.

- Response: realism can treat them as real in their consequences and effects.

- Risk of bias toward dominant “facts.”

- Institutions may define what counts as evidence.

- Response: triangulate sources and examine power shaping knowledge.

- Difficulty proving mechanisms.

- Mechanisms can be hidden and context-sensitive.

- Response: use careful theory, multiple data sources, and plausible causal reasoning.

- Concerns about overconfidence.

- Realism can sound too certain if written poorly.

- Response: state limitations and alternative explanations clearly.

How to Use Realism as a Theoretical Framework – A Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: Align Realism With Your Research Problem

- Use realism when your study is about real-world outcomes shaped by systems.

- Policies and unequal impacts.

- Organizational performance and culture.

- Program effectiveness across different contexts.

- Signals realism is a good match:

- Your topic involves constraints (resources, staffing, law, economics).

- Your outcomes vary by setting and you need to explain why.

- You want causal explanations, not only “what people think.”

Step 2: Write a Framework Statement

- Standard template:

- “This study uses realism as a theoretical framework to examine how structures, contextual conditions, and causal mechanisms shape [outcome] within [setting].”

- Critical realism template (if you want emphasis on structure and power):

- “This study applies realism to explain how institutional structures and social conditions shape the mechanisms that produce [outcome], with attention to contextual variation across [settings].”

- One-sentence justification you can add:

- “This framework is appropriate because the research problem involves outcomes that are influenced by both human agency and real structural constraints.”

Step 3: Define What “Reality” Means in Your Study

- Material conditions (tangible):

- Funding, staffing levels, workload, infrastructure, technology access.

- Institutional conditions (formal):

- Policies, rules, job roles, governance structures, accountability systems.

- Social conditions (informal):

- Norms, expectations, stigma, power dynamics, professional culture.

- Tip for dissertations:

- Define your “real” variables early so your analysis stays consistent.

Step 4: Build a Realist Conceptual Model

- Core realist logic:

- Context → Mechanism → Outcome

- How to expand it:

- Context: setting conditions that enable or block a mechanism.

- Mechanism: the causal process (beliefs, incentives, fear, trust, motivation).

- Outcome: measurable or observable result.

- Example (expanded):

- Context: short staffing + high patient acuity

- Mechanism: rushed handoffs, reduced double-checking, fatigue

- Outcome: increased omissions, delayed interventions, reduced safety

Step 5: Choose Methods That Fit Realist Goals

- Quantitative approach (realist use):

- Identify predictors that represent real constraints or structures.

- Test relationships that map onto your conceptual model.

- Qualitative approach (realist use):

- Explore how participants describe processes that produce outcomes.

- Look for mechanisms and context differences across cases.

- Mixed methods approach (strong realist fit):

- Use quantitative results to identify patterns.

- Use qualitative results to explain mechanisms behind those patterns.

Step 6: Use Realism in Data Analysis (Realist Questions)

- Mechanism-focused questions:

- What processes are producing this outcome?

- What incentives, beliefs, or pressures drive behavior?

- Context-focused questions:

- Under what conditions does the mechanism appear?

- What blocks it in other settings?

- Structure-focused questions:

- What institutional or policy factors shape these processes?

- Where does power sit, and how does it influence outcomes?

- Alternative explanation questions:

- What else could explain this pattern?

- What evidence supports or weakens each explanation?

Step 7: Write Findings in a Realist Way

- Do not only list themes or variables.

- Instead structure findings like this:

- Observed pattern (what happened).

- Context (where, when, and for whom).

- Mechanism (how/why it happened).

- Outcome implications (so what?).

- Example layout:

- Pattern: communication breakdowns increase during peak workload.

- Context: understaffed shifts and high acuity periods.

- Mechanism: time pressure reduces verification and clarity.

- Implication: structured handoff tools may reduce omissions.

Step 8: Strengthen Discussion and Recommendations

- Link recommendations to mechanisms.

- If mechanism is “confusion,” recommend standardization and training.

- If mechanism is “fatigue,” recommend staffing and scheduling changes.

- If mechanism is “policy conflict,” recommend governance alignment.

- Make recommendations realistic.

- Realism demands feasibility: resources, timelines, and accountability must be considered.

- Show transferability carefully.

- Explain which contexts your recommendations apply to.

- Clarify which conditions must be present for success.

Example: Expanded Dissertation-Style Paragraph Using Realism

- Key message:

- The study interprets outcomes as shaped by real structural conditions, not only personal choice.

- How analysis is framed:

- Findings are organized by context, mechanisms, and outcomes.

- What it reveals:

- Institutional rules, resource constraints, and social expectations combine to produce observed patterns.

- Why it matters:

- Explaining mechanisms helps others apply findings in similar settings.

- How it stays accurate:

- The study remains sensitive to contextual differences and avoids overgeneralization.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using Realism

- Mistake: treating realism as “common sense.”

- Fix: define it clearly and name its assumptions (reality, evidence, mechanisms).

- Mistake: staying at the surface level.

- Fix: move from “what happened” to “what caused it” and “under what conditions.”

- Mistake: ignoring context differences.

- Fix: compare settings and explain variation using context-mechanism logic.

- Mistake: confusing correlation with causation.

- Fix: justify causal claims with mechanisms and supporting evidence.

- Mistake: overclaiming certainty.

- Fix: state limitations, alternative explanations, and evidence strength.

- Mistake: using theory only in Chapter 2.

- Fix: apply realism throughout methods, analysis, discussion, and recommendations.

Conclusion

- Realism helps research stay grounded in the world as it actually operates.

- It supports explanation by linking outcomes to mechanisms and structures.

- It strengthens credibility through evidence, transparency, and defensible reasoning.

- It produces practical recommendations because it respects real constraints.

- It is highly useful for dissertations and applied research where context shapes outcomes.