Feminist Epistemology: A Practical, Powerful Guide to How Knowledge Is Made, Challenged, and Improved

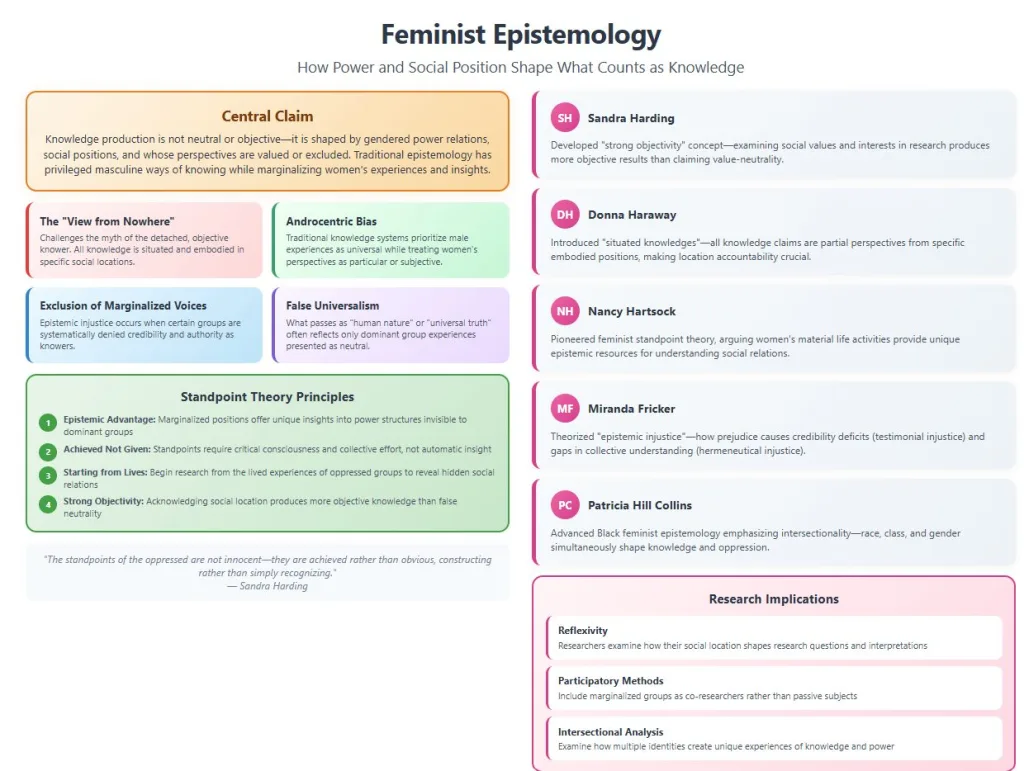

- Feminist epistemology is a field that asks how “knowledge” becomes accepted as knowledge—and then tests whether those pathways are fair, reliable, and complete.

- It examines how evidence is gathered, whose testimony is trusted, which methods are treated as legitimate, and what assumptions are built into research traditions.

- It highlights that knowing is never fully detached from society: gender, power, race, class, disability, sexuality, and institutional authority can shape what people are allowed to know, say, and prove.

- The aim is not to replace knowledge with opinion. It is to strengthen knowledge by improving standards of justification, widening the evidence base, and reducing systematic blind spots.

Why feminist epistemology exists

- Traditional epistemology often imagined the knower as neutral and universal

- Many classic theories treated the ideal knower as detached, rational, and objective.

- Feminist epistemology argues that this “ideal” often mirrors the standpoint of socially powerful groups, even when it claims universality.

- “Neutrality” can hide power

- When a method or institution says it is neutral, it can mask how power shapes:

- who gets research funding,

- whose questions count as “serious,”

- who sits on ethics boards or editorial boards,

- whose writing style is judged “professional.”

- Feminist epistemology treats these as epistemic factors because they influence which claims survive and spread.

- When a method or institution says it is neutral, it can mask how power shapes:

- Exclusion creates distorted knowledge

- If research samples exclude or marginalize certain groups, results can look “general” while actually reflecting only a narrow population.

- Exclusion can produce:

- missing variables,

- misinterpretation of causes,

- policies built on incomplete data,

- harmful “normal ranges” that do not apply to everyone.

- It responds to patterns of dismissed experience

- Historically, women’s reports have been discounted in many contexts, including clinical care, law, and workplace decision-making.

- Feminist epistemology argues that dismissal is not just unfair; it is a route to falsehood, because it blocks access to relevant data.

- It aims to improve inquiry

- Feminist epistemology is reformist at its core: it asks how we can do better research by building:

- stronger objectivity (through accountability),

- more rigorous methods (through inclusive design),

- more reliable interpretation (through reflexivity and transparency).

- Feminist epistemology is reformist at its core: it asks how we can do better research by building:

Key questions feminist epistemology asks

- Who gets treated as credible?

- Feminist epistemology studies how credibility can be unevenly assigned based on stereotypes about who is “rational,” “emotional,” “competent,” or “expert.”

- It examines credibility dynamics such as:

- being interrupted or not taken seriously,

- having one’s expertise questioned,

- being required to provide “extra proof” for the same claim.

- What counts as evidence—and who decides that?

- Some communities privilege only certain forms of evidence (for example, randomized controlled trials) while dismissing other forms (for example, qualitative accounts).

- Feminist epistemology asks:

- When is lived experience a legitimate data source?

- When is it dismissed as “anecdotal” in ways that protect existing power?

- What gets lost when only one method is treated as gold standard?

- Which topics are treated as “important research”?

- Research agendas do not emerge from nowhere.

- Feminist epistemology examines how priorities are shaped by:

- funding structures,

- political interests,

- cultural norms,

- institutional convenience.

- It asks what knowledge is not produced because certain questions are discouraged.

- How do power relations shape knowledge?

- Feminist epistemology stresses that knowledge is made inside systems:

- universities,

- hospitals,

- corporations,

- governments,

- media platforms.

- These systems can reward conformity, punish dissent, and standardize what is publishable—affecting what becomes “true” in practice.

- Feminist epistemology stresses that knowledge is made inside systems:

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowCore principles you can apply immediately

Situated knowing

- Feminist epistemology argues that all knowers are located in a social world.

- Your position affects:

- what you notice,

- what you can access,

- what risks you face for speaking,

- what assumptions feel “obvious.”

- This does not imply relativism.

- It implies epistemic transparency: state where you stand, what you can and cannot claim, and what your methods can actually support.

Reflexivity

- Reflexivity is a disciplined way of checking how your identity, assumptions, and institutional role influence the research process.

- Practical reflexivity questions include:

- What do I assume is “normal” or “typical” here?

- What interpretations feel natural to me—and why?

- How might participants interpret my questions differently because of power differences?

- What outcomes would threaten my expectations, status, or project goals?

Power-aware methods

- Feminist epistemology pushes you to treat power as a methodological issue, not a side note.

- It encourages you to review power at each stage:

- Recruitment: who is reachable and who is excluded by design?

- Consent: do participants feel safe to refuse or withdraw?

- Question framing: are you embedding assumptions in the questions?

- Interpretation: are you privileging institutional narratives over lived experience?

- Publication: who benefits from the results, and who might be exposed to harm?

Epistemic justice

- Epistemic justice focuses on fairness in how people are recognized as knowers.

- Feminist epistemology critiques:

- credibility gaps (some people are trusted less than they should be),

- silencing (people cannot express experiences in accepted terms),

- knowledge extraction (participants provide insight but receive no benefit).

- The goal is to create knowledge practices that are both fairer and more accurate.

Major approaches within feminist epistemology

1) Standpoint theory

- What it argues

- Marginalized groups can develop valuable insight into how power works, because they must navigate it directly.

- Their experiences can reveal what dominant groups overlook because dominance feels “normal.”

- Why it matters

- Standpoint theory is not “marginalized people are always right.”

- It is “social location can reveal blind spots,” especially in systems where power hides itself.

2) Feminist empiricism

- What it argues

- Bias is not solved by pretending it is absent; it is solved by improving research design.

- Feminist empiricism strengthens science through:

- better sampling,

- clearer constructs,

- more careful measurement,

- stronger peer criticism,

- replication and transparency.

- Why it matters

- It shows feminist epistemology can be compatible with scientific rigor.

- It treats feminism as a tool for better reliability and validity.

3) Feminist postmodern and poststructural approaches

- What it argues

- Language and categories shape reality as we study it.

- Terms like “woman,” “reason,” and “objectivity” carry historical baggage and political consequences.

- Why it matters

- These approaches help you avoid:

- treating categories as fixed when they shift across cultures and time,

- building measures that silently exclude people who do not fit the dominant definition.

- These approaches help you avoid:

4) Social epistemology and communities of knowers

- What it argues

- Knowledge is not mainly produced by lone geniuses; it is produced by communities with norms.

- These include:

- journals and peer review,

- disciplines and methods,

- institutions and gatekeepers.

- Why it matters

- If the community is exclusionary, the “consensus” it produces can be systematically biased.

- Feminist epistemology therefore studies institutional knowledge-making, not just individual belief.

Key concepts you’ll see again and again

Objectivity (rethought, not discarded)

- Feminist epistemology critiques the fantasy of a “view from nowhere.”

- It often argues for stronger objectivity by:

- making assumptions explicit,

- using diverse perspectives to catch blind spots,

- creating accountability for methods and interpretations.

- Objectivity becomes a practice—something you do—rather than a personality trait.

Bias

- Feminist epistemology treats bias as multi-layered:

- Individual bias: stereotypes and assumptions shaping interpretation.

- Structural bias: whose work is funded, published, hired, promoted.

- Methodological bias: measures that erase relevant variation or treat dominant experiences as default.

- The aim is not to eliminate all perspective, but to identify distortions and correct them.

Experience as evidence

- Feminist epistemology does not treat experience as automatically authoritative.

- It treats experience as evidence when it is:

- collected systematically (clear sampling, careful interviewing),

- analyzed carefully (coding procedures, transparency),

- triangulated (compared with documents, observations, statistics).

- This prevents the false choice between “only numbers matter” and “anything someone says is true.”

Power and credibility

- Feminist epistemology examines how authority is assigned through:

- credentials and institutional status,

- speaking style and cultural norms,

- stereotypes about rationality and emotion,

- access to platforms and publication.

- It asks: are we rewarding truth, or rewarding social power?

What feminist epistemology changes in research practice

It changes the research question

- It pushes you to ask:

- Who benefits from this framing?

- Who is made invisible by this definition?

- What would the problem look like if we started from different experiences?

- This often produces research questions that are more precise and less biased.

It changes the methods

- Feminist epistemology often supports:

- Qualitative methods to capture meaning, voice, and context.

- Quantitative methods to map patterns and test relationships.

- Participatory designs to reduce extractive research and improve validity through collaboration.

- The central aim is alignment between values (fairness, inclusion) and method (how data are produced).

It changes interpretation

- It warns against:

- universalizing from narrow samples,

- treating “average effects” as equally true for all groups,

- ignoring context that explains why findings occur.

- It promotes careful boundary statements: where your findings apply, where they might not, and why.

It changes research ethics

- It emphasizes ethics as ongoing practice:

- respectful representation of participants,

- avoiding harm through careless reporting,

- sharing results in accessible forms,

- giving participants benefits where possible.

Common critiques—and how feminist epistemology responds

Critique: “It makes knowledge subjective.”

- Feminist epistemology responds:

- all inquiry involves perspective and choices (what to measure, what to ignore),

- pretending neutrality can hide bias,

- better science comes from transparency, critique, and testing assumptions.

Critique: “It is political, so it is not scholarly.”

- Feminist epistemology responds:

- research is already shaped by political and institutional priorities,

- declaring values openly allows better accountability,

- scholarship improves when its hidden commitments are made visible.

Critique: “It replaces truth with identity.”

- Feminist epistemology responds:

- identity is not evidence by itself,

- standpoint helps identify blind spots and missing questions,

- evidence still matters, but the definition of evidence becomes more complete and fair.

Real-world examples of what feminist epistemology can reveal

Healthcare and medicine

- It can explain why:

- diagnostic criteria may reflect one population more than others,

- pain reports can be discounted,

- “normal” baselines are sometimes built from narrow samples.

- It supports better designs:

- diverse recruitment,

- sex- and gender-aware analysis,

- integration of qualitative insight into clinical research.

Workplace research

- It can reveal how:

- “leadership” measures reward assertive communication styles as default,

- evaluation systems penalize different styles as “less professional.”

- It encourages:

- redefining constructs,

- expanding indicators of competence,

- examining how organizational power shapes performance judgments.

Technology and data science

- It critiques how:

- historical discrimination becomes encoded in datasets,

- labels treated as “ground truth” may reflect biased institutions.

- It supports:

- dataset audits,

- fairness testing,

- rethinking what counts as a valid target variable.

Education

- It asks:

- whose knowledge is included in curricula,

- whose participation styles are valued,

- whose language practices are treated as “correct.”

- It supports inclusive pedagogy grounded in epistemic fairness.

How to use feminist epistemology as a theoretical framework in a research paper or dissertation

Step 1: Define why it fits your topic

- Use feminist epistemology when your topic involves:

- unequal access to voice and credibility,

- knowledge gaps caused by exclusion,

- institutional power shaping evidence,

- contested expertise (who is believed, and why).

Step 2: Strengthen your framework statement

- Framework statement (expanded, still adaptable)

- This study is guided by feminist epistemology, which examines how social location, institutional power, and credibility practices shape what is accepted as knowledge. This framework informs the research questions, directs attention to whose experiences are treated as legitimate evidence, and supports reflexive analysis of how the research process itself may reproduce or challenge epistemic exclusion.

Step 3: Translate it into research questions

- Feminist epistemology often produces questions such as:

- How do credibility norms in this setting shape what is believed?

- Which experiences are missing from the literature, and what structures explain that absence?

- How do gendered assumptions influence definitions, measurement choices, and interpretation?

Step 4: Align methods with the framework

- Choose methods that match the framework’s claims:

- Qualitative to capture voice, meaning, silences, and credibility dynamics.

- Mixed methods to connect lived experience with measurable patterns.

- Participatory to improve trust, reduce extraction, and strengthen validity through shared interpretation.

Step 5: Build a reflexivity plan

- Document:

- your positionality and assumptions,

- how you handled power in recruitment and interviews,

- how you ensured participants could disagree or withdraw safely,

- how you prevented misrepresentation in reporting.

Step 6: Use it in analysis and discussion

- In findings:

- treat participants as knowledge producers, not mere data points.

- In discussion:

- show how dominant assumptions shaped previous research,

- explain how your study corrects, extends, or complicates existing accounts.

Step 7: Make your contribution explicit

- Examples of contributions aligned with feminist epistemology:

- redefining a concept to avoid built-in gender bias,

- mapping credibility pathways (who is believed and why),

- identifying missing variables caused by exclusion,

- demonstrating how reflexive methods improved interpretive validity.

“Point-form but explained” mini-template for your dissertation chapter

Theoretical lens

- Feminist epistemology frames knowledge as socially situated and shaped by power relations, guiding how evidence, credibility, and “objectivity” are evaluated in this study.

Assumptions

- Knowledge is produced within social contexts rather than outside them. Objectivity is strengthened through transparency, reflexivity, inclusion of diverse standpoints, and critical scrutiny of institutional norms.

Methodological implications

- The research design uses methods that capture lived experience and reduce epistemic exclusion. Reflexive documentation and triangulation are used to improve reliability, validity, and ethical accountability.

Analytic focus

- Analysis attends to silences, credibility dynamics, and institutional practices that shape which accounts are treated as legitimate knowledge, and how interpretations may reproduce or challenge power.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Using it only as a label

- If feminist epistemology is your framework, it must shape:

- research questions,

- sampling logic,

- data collection,

- analysis decisions.

- If feminist epistemology is your framework, it must shape:

- Overclaiming standpoint

- Avoid implying any group has automatic truth.

- Use standpoint to locate blind spots and improve evidence, not to replace evidence.

- Neglecting intersectionality

- Gender rarely acts alone.

- Add an intersectional lens where relevant so findings do not treat “women” as a single uniform category.

- Forgetting rigor

- Strong feminist epistemology work is methodologically explicit:

- clear audit trail,

- transparent coding,

- justification for sampling,

- triangulation across data types.

- Strong feminist epistemology work is methodologically explicit:

Frequently used sentences you can adapt

- On purpose

- This study uses feminist epistemology to examine how credibility norms and institutional power shape what counts as evidence within the research context.

- On methods

- In line with feminist epistemology, the design attends to voice, exclusion, and reflexivity by documenting how recruitment, questioning, and interpretation may influence whose knowledge becomes visible.

- On validity

- Interpretive validity is strengthened through transparency of analytic decisions, triangulation of evidence, and reflexive accounting of positionality and power relations.

Closing takeaway

- Feminist epistemology is not only about adding women to research.

- It is about improving the quality of knowledge by examining how credibility, evidence standards, and institutional power shape what becomes accepted as truth.

- When applied well, it produces research that is more accurate, more inclusive, and more ethically responsible, especially in areas where people’s voices have historically been ignored or discounted.