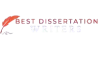

Phenomenology as a Theory: A Clear, Practical, and Research-Focused Guide

Introduction to phenomenology

- Phenomenology is a theoretical approach that focuses on how people experience the world from their own point of view. It is less interested in what an experience should mean according to outside definitions and more interested in what it actually feels like to the person living it. In this sense, phenomenology treats experience as a primary source of insight into human life.

- Rather than explaining behavior mainly through external causes such as social forces, biology, or measurable stimuli, phenomenology asks what the experience is like for the person. It looks at how reality is consciously lived, noticed, felt, and interpreted. This includes how people describe meaning in ordinary life, how they make sense of events, and how they experience emotions, relationships, and identity.

- As a theory, phenomenology is widely used because many important human problems cannot be fully understood through measurement alone. It is used in philosophy to examine consciousness and meaning, in psychology to explore subjective experience, in education to understand learning as lived practice, in nursing and health sciences to study illness and care experiences, and in sociology to examine how social life is experienced from within.

- This article explains phenomenology using structured points so it is easy to follow and apply. It also shows how phenomenology can be used as a rigorous academic framework, meaning it can shape your research problem, guide your methods, and strengthen how you interpret findings in a research paper or dissertation.

What is phenomenology as a theory?

- Phenomenology is a theory of knowledge and experience that studies phenomena as they appear to human consciousness. A “phenomenon” here means anything that shows up in experience, such as pain, hope, fear, belonging, confusion, shame, relief, or feeling respected. The focus is not just on what happens, but on how it is experienced and understood.

- The theory assumes that reality is not simply “out there” to be measured like an object independent of human awareness. Instead, reality is actively experienced and given meaning by individuals as they perceive, interpret, and respond to the world. This does not mean facts do not exist. It means that human life is shaped by how facts are encountered and experienced.

- In theoretical terms, phenomenology tries to describe experience without forcing it into predefined categories or quick explanations. For example, instead of treating grief as only a set of stages or symptoms, phenomenology would explore how grief is lived in the body, how time feels during grief, how relationships change, and how meaning shifts.

- The aim is depth of understanding rather than prediction or generalization. Phenomenology tries to illuminate the structure and meaning of experience so that readers can better understand what a phenomenon is like and why it matters in human life.

Philosophical origins of phenomenology

- Phenomenology emerged in the early twentieth century partly as a reaction against positivism, which prioritized scientific measurement and often treated subjective experience as unreliable or secondary. Early phenomenologists argued that reducing human life to only what can be measured leaves out the core of what it means to be human.

- It challenged the idea that objective measurement alone can explain complex experiences such as love, moral conflict, suffering, identity, belonging, or faith. These experiences involve meaning, interpretation, and context, and they are often lived in ways that cannot be captured well through surveys or experiments alone.

- The theory developed within continental philosophy, which focused more on meaning, existence, language, history, and culture than on purely analytic or empirical methods. Over time, phenomenology influenced many social science disciplines and became a major foundation for qualitative research, especially research concerned with lived experience.

Edmund Husserl and transcendental phenomenology

- Phenomenology was formally founded by Edmund Husserl, who argued that inquiry should return “to the things themselves.” By this, he meant that researchers and philosophers should return to how things appear in experience rather than relying only on theories, assumptions, or inherited explanations.

- Husserl’s approach emphasized careful description of experience as it appears to consciousness. The goal is to identify what is present in experience and how it is present, rather than immediately interpreting it through social theories, medical labels, or moral judgments.

- He introduced the idea of bracketing, meaning the researcher tries to suspend or hold back assumptions about the external world so they can focus on describing experience more clearly. Bracketing does not require the researcher to forget everything they know. It requires disciplined awareness of assumptions, so the researcher does not impose them on participants’ experiences.

- In Husserlian phenomenology, the goal is to identify the essential structures of experience, sometimes called essences. These are the core features that make an experience what it is. For example, an essence of anxiety might involve a future-oriented sense of threat, bodily tension, and uncertainty, even though each person’s anxiety looks different in details.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowMartin Heidegger and interpretive phenomenology

- Heidegger expanded phenomenology by shifting attention toward being, existence, and meaning in everyday life. He argued that humans are not detached observers of the world. They are beings who live within the world through relationships, responsibilities, language, and culture.

- He emphasized that people are always situated. This means experience is shaped by social roles, history, community norms, and personal biography. A person’s experience of “stress,” for example, can be inseparable from their workplace expectations, family responsibilities, cultural beliefs, and identity.

- Unlike Husserl, Heidegger rejected the idea that complete bracketing is possible. He argued that interpretation is always part of understanding. People interpret their lives constantly, and researchers interpret participants’ accounts when they analyze them.

- This form of phenomenology is often called hermeneutic or interpretive phenomenology. It is especially common in applied fields like nursing, education, and social work because it acknowledges that meaning is shaped by context and that understanding emerges through interpretation rather than pure description.

Merleau-Ponty and embodied experience

- Merleau-Ponty contributed by emphasizing the body as central to experience. He argued that we do not experience the world as minds floating above reality. We experience it through a living body that moves, senses, reacts, and engages with the environment.

- Perception, in this view, is not purely mental. It is grounded in bodily engagement. This is especially important for understanding experiences like chronic pain, disability, fatigue, panic, hunger, athletic performance, pregnancy, or trauma, where the body is not just present but central to meaning.

- This perspective influenced health sciences, psychology, education, and occupational therapy because it provides language for describing how experience is felt physically and how bodily life shapes identity and agency.

- Phenomenology here highlights movement, sensation, and lived bodily awareness. For example, instead of describing anxiety only as a thought pattern, it would include how anxiety tightens the chest, changes breathing, alters attention, and reshapes the sense of time and safety.

Jean-Paul Sartre and existential phenomenology

- Sartre applied phenomenology to questions of freedom, responsibility, and selfhood. He focused on how people experience themselves as agents who must choose, and how this can create both possibility and distress.

- He explored experiences such as choice, anxiety, shame, and self-deception. These are not treated as abstract concepts but as lived realities that shape how people act and understand themselves.

- His work linked phenomenology with existentialism and social critique. He examined how social expectations, power, and interpersonal dynamics influence lived experience, including how people experience being judged by others.

- This strand emphasizes agency and lived meaning in human action. It is often useful when studying experiences involving moral conflict, identity pressure, stigma, or life transitions where people must make difficult choices.

Core assumptions of phenomenology

- Phenomenology rests on foundational theoretical assumptions that shape how it studies human life. These assumptions guide what counts as evidence, what questions are worth asking, and how findings should be interpreted.

Experience is central

- Human experience is treated as a primary source of knowledge, not as a weak substitute for “objective” data. Phenomenology argues that to understand many human realities, you must understand how they are lived.

- Lived experience is therefore legitimate and meaningful data. The details of how people describe feelings, perceptions, and meaning are not distractions. They are the point.

Reality is subjectively interpreted

- Meaning is created through perception and consciousness. Two people can face the same event but experience it differently based on their history, expectations, relationships, and interpretations.

- Phenomenology rejects the idea that there is a single, purely objective reality that fully explains human life. It does not deny external reality. It argues that for human sciences, reality includes meaning as lived and interpreted.

Context matters

- Experience is shaped by time, place, culture, and relationships. A person’s experience of “support” depends on who gives it, how it is offered, and what it means in that cultural setting.

- Phenomenology studies experience as it occurs in real-world contexts. It tries to preserve complexity rather than flatten experience into isolated variables.

The concept of lived experience

- Lived experience refers to how life is actually felt and understood in everyday reality. It includes how experiences unfold through time, how they affect identity, how they are remembered, and how they shape relationships.

- Lived experience includes emotions, thoughts, memories, bodily sensations, and social meaning. It also includes subtle features that people may struggle to express, such as feeling “out of place,” feeling “seen,” or feeling “unsafe” without obvious evidence.

- The theory values rich, first-person descriptions rather than abstract explanations. Phenomenology assumes that language, stories, metaphors, pauses, and emotional expressions can reveal important structures of meaning.

- Phenomenology aims to reveal what an experience is like from the inside. The goal is not simply to summarize what participants said, but to illuminate the deeper meaning and structure of the experience so readers can understand it more fully.

Consciousness and intentionality

- Phenomenology assumes that consciousness is always directed toward something, meaning people are always conscious of objects, events, memories, hopes, fears, or relationships. This directedness is called intentionality.

- Thoughts, perceptions, and emotions are intentional acts connected to situations or objects. Fear is fear of something. Hope is hope for something. Grief is grief for someone or something lost. Even confusion has a focus, such as uncertainty about a decision or identity.

- This idea helps researchers explore how people relate meaningfully to their world. Instead of treating emotions as internal “states,” phenomenology explores what emotions reveal about the person’s situation, values, and sense of reality.

- Phenomenology therefore studies relationships between the experiencer and what is experienced. It asks how the world is present to the person, how meaning forms, and how experience shapes action.

Methods associated with phenomenology

- Although phenomenology is a theory, it strongly influences research methodology because it implies certain ways of gathering and interpreting data that fit its focus on lived meaning.

In-depth interviews

- Participants are invited to describe experiences in their own words, often with prompts that encourage detail. Researchers may ask participants to recall specific moments, feelings, and meanings rather than general opinions.

- The goal is to capture reflective, concrete accounts. Good phenomenological interviewing encourages participants to describe “what it was like,” “what stood out,” “what changed,” and “how it felt in the body and mind.”

Reflective analysis

- Researchers engage deeply with participants’ descriptions through careful reading, reflection, and memo-writing. They pay attention to tone, metaphor, emotional shifts, contradictions, and silences.

- Phenomenology requires attentiveness to nuance and meaning because small details can reveal large structures of experience, such as how time, identity, or relationships are experienced.

Thematic interpretation

- Patterns of meaning are identified across participants, not to reduce uniqueness but to reveal shared structures. Themes represent important dimensions of the lived experience, such as uncertainty, loss of control, relational tension, or embodied discomfort.

- Themes reflect shared aspects of lived experience and are often presented alongside rich descriptions and participant quotes to preserve depth and credibility.

Phenomenology in qualitative research

- Phenomenology is most commonly used within qualitative research designs because it fits questions that are meaning-centered rather than measurement-centered. It is chosen when the researcher wants understanding of experience, not numeric comparison.

- It is used when the research question asks how people experience a phenomenon, what meaning they assign to it, and how it shapes their lives. This includes questions about care, learning, trauma, leadership identity, patient experience, grief, resilience, migration, or stigma.

- It is widely used in nursing, psychology, education, and social work because these fields frequently deal with human experiences that are complex, emotional, and context-bound. Phenomenology helps capture the realities behind terms like “patient-centered care” or “professional transition.”

- Phenomenology is especially useful for studying experiences that are difficult to measure but important to understand, such as feeling safe in a hospital, adapting to chronic illness, navigating infertility, surviving violence, or becoming confident in a new professional role.

Data analysis in phenomenological studies

- Analysis focuses on meaning rather than frequency. It is not about how many participants said a phrase. It is about what the phrase reveals about the structure of the experience.

- Researchers read and reread transcripts to immerse themselves in the data. This immersion helps the researcher remain close to participants’ words and avoid rushing to interpretation.

- Significant statements are identified and clustered into themes that capture key dimensions of the phenomenon. Researchers often move back and forth between parts of the text and the whole, ensuring the themes remain grounded in participants’ descriptions.

- The final outcome is a rich description of the essence of the experience. Depending on the approach, this may include a detailed narrative of what the experience is like, what meanings shape it, and what contextual conditions influence it.

Strengths of phenomenology as a theory

- Phenomenology provides deep insight into human experience, especially experiences that are subjective, emotional, or complex. It can reveal dimensions of life that are invisible in purely quantitative studies.

- It respects participants’ voices and perspectives. Participants are treated as meaning-makers, and their accounts are not reduced to symptoms, categories, or stereotypes.

- The theory is flexible across disciplines while remaining conceptually rigorous. It can be used to study health, education, leadership, technology, culture, religion, or social identity, as long as the focus is lived meaning.

- Phenomenology allows complex, emotional, and subjective phenomena to be studied systematically. Through careful methodology, transparent analysis, and reflexivity, it produces credible and academically valuable findings.

Limitations of phenomenology

- Phenomenology does not aim for statistical generalization. Its goal is not to claim that findings apply to all people, but to offer deep understanding that may be transferable to similar contexts.

- Findings may be influenced by researcher interpretation, especially in interpretive approaches. This is why reflexivity is essential, meaning the researcher must be transparent about assumptions, position, and interpretive choices.

- The approach requires discipline and skill. Poorly conducted phenomenology can become vague or overly philosophical. Strong phenomenological studies maintain clarity, depth, and clear links between data and interpretation.

- Despite these limits, phenomenology remains valuable because it explains meaning and experience in ways that other theories often miss, especially in applied fields where understanding lived reality improves practice and policy.

Using phenomenology as a theoretical framework in research

- Phenomenology can be adopted as a theoretical framework that shapes the entire study, not just the method. When used as a framework, it supports coherence across research problem, questions, design, analysis, and conclusions.

Framing the research problem

- The study is positioned around understanding lived experience, often addressing a gap where experience is misunderstood, oversimplified, or ignored.

- Research questions focus on how participants experience a phenomenon, what it means to them, and how it shapes their decisions, identity, relationships, or wellbeing.

Guiding methodology

- The choice of qualitative design aligns with the theory’s emphasis on meaning. Sampling often targets participants with direct lived experience of the phenomenon.

- Data collection emphasizes depth and reflection through interviews, narratives, reflective journals, or observations, depending on what best captures experience.

Shaping analysis and interpretation

- Findings are discussed in terms of meaning and essence. The analysis aims to illuminate core structures of the experience, such as how time is experienced, how the body is experienced, or how identity is reshaped.

- Phenomenology provides coherence by offering a consistent lens through which participants’ accounts are understood, ensuring the study does not drift into unrelated explanations.

Enhancing academic rigor

- The framework justifies interpretive choices and clarifies what the study can and cannot claim. It supports methodological transparency, including how themes were derived and how researcher bias was handled.

- It demonstrates philosophical grounding in the dissertation, strengthening the scholarly legitimacy of the work and showing that the study is not simply “interview-based,” but theoretically anchored.

Key Takeaways

- Phenomenology is a powerful theory for exploring how people experience and make sense of their world. It clarifies meaning, illuminates lived reality, and helps researchers understand human life from the inside.

- It challenges purely objective explanations by showing that experience involves perception, interpretation, embodiment, and context. These elements shape what reality feels like and how people act within it.

- As a theoretical framework, phenomenology strengthens qualitative research by providing philosophical depth and conceptual clarity. It ensures the study remains focused on lived meaning rather than surface-level description.

- When applied carefully, phenomenology enables researchers to produce rich, credible, and insightful academic work that can inform practice, education, policy, and future research.