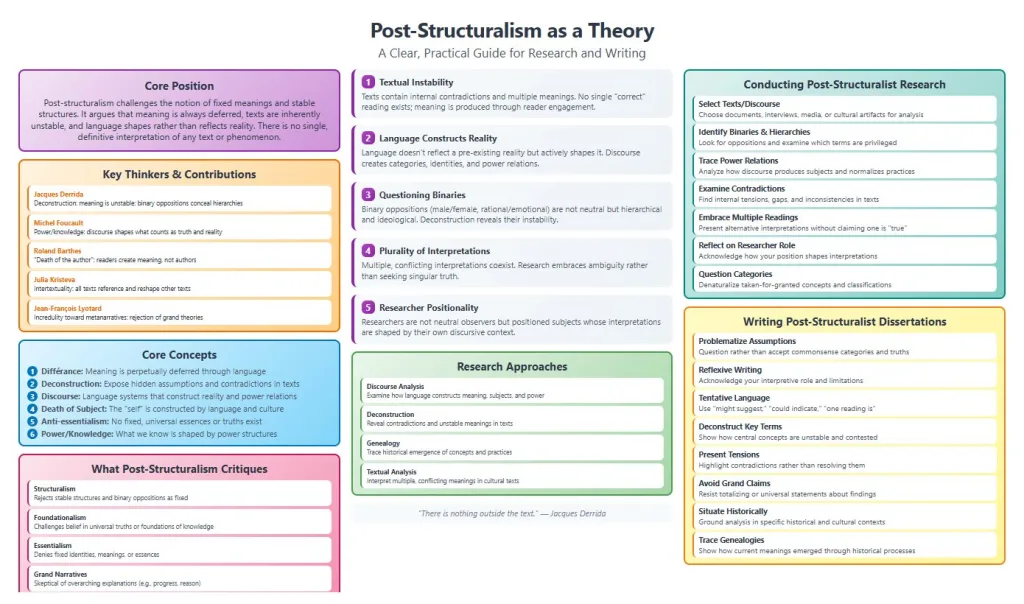

Post-structuralism as a theory: a clear, practical guide for research and writing

- Post-structuralism is a way of thinking that asks you to treat “meaning” as something produced, negotiated, and contested rather than something fixed and waiting to be discovered.

- In simple terms, post-structuralism argues that language, culture, and power shape what counts as “truth,” “common sense,” and even “identity,” so researchers should study how those meanings are made.

- This perspective is widely used in the social sciences and humanities because it helps explain why the same issue can be interpreted very differently across settings, time periods, and groups.

- This theory explains how meaning, knowledge, and identity are constructed through language and social practices, and how those constructions can shift across contexts and time.

Origins and background

- It developed as scholars began questioning the idea that deep, stable structures (like universal rules of language or culture) could fully explain human life.

- It grew out of debates in linguistics, anthropology, psychoanalysis, and literary theory, but it pushed further by emphasizing instability, difference, and the politics of interpretation.

- It also expanded alongside critiques of “neutral” knowledge, arguing that institutions and histories can influence what gets treated as evidence and what gets labeled as truth.

Post-structuralism versus structuralism

- Structuralism focuses on underlying systems (for example, language rules) that organize meaning, often assuming those systems are relatively stable.

- Post-structuralism agrees that systems matter, but it argues that systems are not closed or permanent; meanings can slip, change, and depend on context.

- Structuralism often seeks general patterns; post-structuralism often asks what gets excluded, silenced, or made “unthinkable” by those patterns.

- A quick memory hook: structuralism looks for structure; post-structuralism looks for how structure is produced, maintained, and disrupted.

Core assumptions (explained simply)

- Meaning is not fixed

- Words do not carry one stable meaning forever; meaning depends on use, context, and relationships to other words and ideas.

- This is why definitions can feel “obvious” in one setting and become controversial in another.

- Language does not just describe reality; it helps create it

- When institutions label people (for example, “at-risk,” “noncompliant,” “gifted,” “illegal”), those labels can shape treatment, expectations, and self-understanding.

- A post-structuralism approach therefore treats language as a social force, not only a description.

- Knowledge and power are connected

- What counts as “expert knowledge” is often produced inside systems (schools, hospitals, courts, media) that have authority and rules.

- A post-structuralism analysis asks: who benefits when one explanation becomes dominant, and who is harmed by it?

- Identities are constructed and multiple

- People are positioned through roles and norms (for example, “good patient,” “ideal student,” “responsible parent”), and those positions can shift across contexts.

- This helps explain why individuals can feel tension between labels, roles, and lived experience.

- Categories are political tools

- Categories such as “normal/abnormal” or “healthy/unhealthy” can organize resources, rights, surveillance, and stigma.

- The key question is not only “Is the category accurate?” but “What does the category do in practice?”

Key concepts you’ll see in this approach

- Discourse

- Discourse means more than talk; it includes shared ways of speaking, writing, and thinking that define what is reasonable, true, and possible.

- In research, discourse analysis examines how repeated patterns of language shape policy, practice, and everyday interactions.

- Power

- Power is not only “top-down” control; it can be embedded in routines, standards, documentation, and “best practice” language.

- Power often shows up in who gets to name a problem, set a standard, or define success.

- Subjectivity and subject positions

- Subjectivity refers to how people become “subjects” through expectations and language, such as being constructed as “compliant,” “risky,” or “competent.”

- A post-structuralism reading shifts attention from “what a person is” to “how a person is positioned.”

- Difference and binaries

- Meaning is often organized through contrasts (for example, “professional” makes sense partly by implying what is “unprofessional”).

- Studying difference helps you see who is included, excluded, praised, or blamed by institutional language.

- Deconstruction

- Deconstruction examines how concepts rely on hidden assumptions and binary oppositions (for example, rational/emotional, normal/deviant).

- The goal is not to “destroy” meaning, but to reveal complexity and show how meaning depends on what is pushed to the margins.

- Intertextuality

- Texts echo other texts: policies borrow from guidelines; media repeats familiar scripts; research repeats inherited framings.

- Tracing those echoes helps you understand how certain stories gain authority.

- Genealogy and historicizing

- Genealogy examines how a concept (like “risk,” “responsibility,” or “professionalism”) developed historically through conflicts, reforms, and institutional needs.

- This is useful when a present-day “truth” seems natural but has a traceable history.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowMajor thinkers and what they offer (in practical terms)

- Michel Foucault

- Focus: discourse, institutions, power/knowledge, and how “normal” is produced.

- Practical use: analyze policies and professional language to see how they shape behavior and identity.

- Jacques Derrida

- Focus: deconstruction, instability of meaning, and how binaries structure thought.

- Practical use: read texts (policy, interviews, media) for contradictions, silences, and taken-for-granted hierarchies.

- Roland Barthes

- Focus: cultural myths and how texts create meanings beyond author intention.

- Practical use: examine how cultural narratives shape what audiences interpret as natural or true.

- Julia Kristeva

- Focus: intertextuality and subject formation.

- Practical use: explore how identity is produced through social scripts and symbolic boundaries.

- Judith Butler

- Focus: performativity, especially how gender is produced through repeated acts and norms.

- Practical use: study how norms become “real” through repetition and social reinforcement.

What this theory looks like in real settings

- Education

- Instead of asking only “Which method works best?”, you can ask how “achievement,” “ability,” and “behavior” are defined, measured, and rewarded.

- You can then analyze how those definitions position some learners as “capable” and others as “problematic,” and what alternatives are available.

- Health and nursing

- Instead of treating “non-adherence” as a personal flaw, you can examine how medical language, institutional routines, and stigma shape patient choices and interactions.

- This can reveal how certain labels limit trust, reduce shared decision-making, or discourage disclosure.

Why researchers use this approach

- It helps you study “how” rather than only “what”

- It shifts focus from measuring a variable to analyzing the processes that make that variable meaningful in the first place.

- It reveals hidden assumptions

- It helps uncover what a policy or practice treats as obvious, natural, or neutral.

- It supports equity-focused analysis

- It highlights how categories and labels can privilege some groups while disadvantaging others through everyday language and routine decisions.

- It strengthens critical reading and writing

- It trains you to read documents, interview transcripts, and media texts for framing, boundaries, and silences, not only for “facts.”

Common critiques (and practical ways to respond)

- “It is too abstract”

- Response: define your core concepts early (for example, discourse, subject positioning, power/knowledge) and show exactly how each concept guides your analysis.

- “It rejects reality”

- Response: clarify that post-structuralism does not deny lived experience; it studies how experience becomes intelligible and actionable through language and institutions.

- “It leads to relativism”

- Response: ground your claims in data (texts, interviews, observations) and explain why your interpretation fits the evidence better than alternatives.

- “It cannot generalize”

- Response: emphasize transferability: your goal is to deepen understanding of meaning-making in a context so readers can judge relevance to similar contexts.

Methods that align well with post-structuralism

- Discourse analysis

- Best when you want to study how language shapes policy, practice, and identity (for example, “patient safety,” “risk management,” “merit,” “inclusion”).

- Critical policy analysis

- Best when you want to explore how policy frames a “problem,” who is blamed, and what solutions become possible or impossible.

- Textual analysis and deconstruction

- Best for documents, media, guidelines, and organizational communications where binaries and assumptions matter.

- Narrative and interview analysis (with a discursive focus)

- Best when you want to analyze how people use available cultural “stories” to explain themselves and others.

How to use post-structuralism as a theoretical framework in a research paper or dissertation

- Step 1: Write a clear theoretical position

- State that post-structuralism will guide your study of how meanings are produced through language, practices, and power relations in your chosen context.

- Name 3–5 concepts you will use repeatedly (for example, discourse, subject positions, binaries, power/knowledge, deconstruction) and give plain-language definitions.

- Step 2: Translate the theory into research questions

- Strong post-structuralism questions often start with “how”:

- How is a key concept defined and circulated in this setting (for example, “quality,” “risk,” “success,” “professionalism”)?

- How do these definitions position certain groups as responsible, deviant, deserving, or deficient?

- How do people negotiate, resist, or reproduce these meanings in everyday practice?

- Strong post-structuralism questions often start with “how”:

- Step 3: Choose data that captures meaning-making

- Prioritize materials where language and norms are visible:

- Policies, guidelines, training manuals, and institutional forms

- Meeting minutes, emails, and public statements

- Media coverage, websites, and social media posts (when relevant)

- Interview and focus group transcripts, especially around experiences of labeling and identity

- Observations of routine interactions where standards are enforced

- Prioritize materials where language and norms are visible:

- Step 4: Build an analytic strategy that matches post-structuralism

- Identify recurring terms, metaphors, and binaries (for example, “compliant/noncompliant,” “deserving/undeserving,” “safe/unsafe”).

- Map how authority is established (for example, through statistics, professional titles, “evidence-based” language, or moral claims).

- Look for silences and absences: what is not said, and what cannot easily be said within this discourse?

- Examine subject positions: what kinds of “good” and “bad” identities are made available to participants?

- Show moments of instability: contradictions, shifting meanings, contested definitions, and forms of resistance.

- Step 5: Explain quality and rigor in a way that fits the framework

- Transparency: describe how you selected texts, participants, and extracts, and how you moved from data to interpretation.

- Reflexivity: explain how your role and assumptions shape what you notice and how you interpret it.

- Thick description: provide enough context so readers can judge transferability to other settings.

- Step 6: Link findings to implications

- In post-structuralism research, implications often focus on changing language, categories, and institutional routines.

- Explain what would change if an organization used alternative framings (for example, shifting from blame to support, or from deficits to strengths).

- Step 7: Make the framework visible across chapters

- Introduction: justify why post-structuralism fits the problem and define your key concepts early.

- Methodology: explain your data sources and analytic steps clearly, including reflexivity.

- Findings and discussion: present discourses and subject positions with extracts, then show what changes your analysis suggests.

Example dissertation topics that fit post-structuralism

- Health and nursing

- How labels such as “noncompliance” are constructed in care and how patients negotiate those labels.

- Education

- How “inclusion” is framed in school policy and how learners experience inclusion and exclusion.

- Social policy

- How policies construct “deserving” versus “undeserving” recipients and how this shapes service delivery.

A checklist to keep your writing grounded

- Define your key concepts and use them consistently.

- Show how power operates through language, standards, and routines.

- Make your interpretation process visible and defensible.

Common mistakes (and quick fixes)

- Mistake: using post-structuralism as a label without doing the analysis

- Fix: show discourse patterns, binaries, subject positions, and power/knowledge connections in your findings, not just in your introduction.

- Mistake: turning everything into “opinion”

- Fix: anchor claims in texts and transcripts, quoting short extracts to show evidence for your interpretation.

- Mistake: avoiding practical implications

- Fix: propose changes in framing, policy language, communication practices, and institutional routines, and explain why those changes matter.

Key Takeaways

- Post-structuralism is most powerful when your research problem involves contested meanings, identity labels, institutional language, and subtle power.

- Used carefully, post-structuralism helps you produce analysis that is both critical and practical: it shows how social realities are built through discourse and how those realities can be reshaped.

- If you explain your concepts clearly and make your analytic steps transparent, post-structuralism can function as a strong, defensible theoretical framework for a research paper or dissertation.