Social Constructivism: A Clear, Practical, and Research-Ready Guide

- Social constructivism is used across education, sociology, psychology, communication studies, and research methodology because it explains how people come to “know” what they know.

- Instead of treating knowledge as a fixed object “out there,” social constructivism focuses on how meaning is built:

- through conversation and negotiation

- through shared routines and institutions (schools, workplaces, families)

- through culture, norms, and values that shape what counts as “true” or “reasonable”

- This matters because many real-world issues are not purely technical.

- For example, ideas like “good leadership,” “professionalism,” “mental illness,” or “quality education” depend heavily on shared social definitions.

- The approach also explains why the same information can produce different interpretations.

- People interpret evidence through language, past experiences, and community expectations.

- In practice, this article helps you:

- understand the theory in plain language

- spot it in everyday life

- apply it in teaching, training, interviews, and academic research

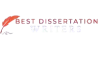

What Is Social Constructivism?

- Social constructivism is a theory of learning and knowledge that argues meaning is created through interaction rather than discovered as a universal, context-free fact.

- It assumes people do not simply “absorb” knowledge.

- They interpret, question, test, revise, and confirm ideas with others.

- Learning becomes a process of making sense together.

- Knowledge is shaped by:

- social interaction (discussion, disagreement, feedback, collaboration)

- language (labels, categories, explanations, narratives)

- culture (norms about what is polite, moral, credible, or acceptable)

- history (what a community has valued and repeated over time)

- A simple way to think about it:

- “What we know” is strongly influenced by “how we talk” and “who we talk with.”

- This does not mean reality is imaginary.

- It means the meaning people assign to events, experiences, and evidence is shaped socially.

Core Assumptions of Social Constructivism

Knowledge is socially constructed

- Social constructivism argues that knowledge is built through shared meaning-making.

- Understanding grows when people:

- compare perspectives

- justify claims

- challenge assumptions

- co-create explanations

- “Truth” often functions like an agreement within a community.

- A claim becomes accepted when it fits evidence and fits the community’s standards for credibility.

- Example:

- In one field, a “strong argument” may mean statistical significance.

- In another, it may mean depth of interpretation and rich context.

Language shapes meaning

- Language does not only describe reality.

- It also organizes it.

- Words and labels influence what people notice and what they ignore.

- If a behavior is labeled “disruptive,” it can trigger discipline.

- If it is labeled “distress,” it can trigger support.

- Communication builds shared frameworks:

- definitions (what something “is”)

- explanations (why it happens)

- expectations (what should happen next)

- This is why social constructivism pays close attention to:

- discourse (how people speak about topics)

- narratives (the stories people use to explain events)

- categories (how groups are named and treated)

Learning is context-dependent

- Meaning is tied to the environment where it is developed.

- Context includes:

- cultural norms

- institutional rules

- power relationships

- resource availability

- group identities and roles

- Knowledge that works well in one setting may not transfer cleanly to another.

- A communication style that works in one workplace may fail in another due to different norms.

- This context focus is a key difference between social constructivism and theories that treat learning as a purely internal process.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowHistorical Origins and Key Thinkers in Social Constructivism

Lev Vygotsky

- Social constructivism is strongly associated with Vygotsky’s work on the social foundations of learning.

- Key idea: learning begins socially, then becomes internal.

- First, the learner participates in shared thinking.

- Later, the learner can perform similar thinking independently.

- Vygotsky highlighted that tools mediate learning:

- language

- symbols

- cultural practices

- teaching routines

- His work supports practical approaches like:

- guided practice

- peer learning

- structured discussion

Later theorists and expansions

- Later scholars widened social constructivism beyond classroom learning.

- They explored how knowledge is shaped by:

- institutions (schools, hospitals, courts, media)

- culture (dominant values and norms)

- discourse (what can be said, and what becomes “normal”)

- power (who gets believed, who gets ignored, whose knowledge counts)

- This is why the theory is common in:

- sociology and anthropology

- qualitative research

- organizational and professional studies

Social Constructivism in Education

Classroom learning as collaboration

- Social constructivism views learning as something learners do together rather than something teachers deliver.

- Effective learning settings include:

- discussion that invites multiple viewpoints

- group problem-solving with clear roles

- peer feedback and peer teaching

- activities that require justification (“Why do you think that?”)

- The teacher’s role shifts toward:

- guiding

- scaffolding

- prompting deeper explanation

- building a safe environment for questions and mistakes

Active learning approaches

- Social constructivism aligns with approaches that treat students as active participants:

- problem-based learning (learning through real problems)

- inquiry learning (learning through investigation)

- project-based learning (learning through building a product or solution)

- peer instruction (learning by explaining to classmates)

- Why these work:

- they force learners to make meaning, not just repeat content

- they create chances to test ideas against others’ reasoning

- they make misunderstanding visible early, so it can be corrected

Assessment implications

- Under social constructivism, assessment should check understanding, not just recall.

- Useful assessment strategies include:

- reflective writing (how thinking changed)

- oral defense (explaining and justifying reasoning)

- portfolios (evidence of growth over time)

- collaborative products with clear individual contributions

- Feedback becomes a dialogue:

- not only “right/wrong”

- but “how did you reason?” and “what could strengthen your explanation?”

Social Constructivism in Research

Understanding multiple realities

- Social constructivism fits research topics where experiences differ by person, group, or setting.

- It assumes:

- people interpret events through culture and identity

- meanings shift across contexts

- the same situation can produce different “realities” for different participants

- Research focus often becomes:

- how people describe their experiences

- how they explain causes and consequences

- how their social world shapes what they believe and do

Common research methods

- Methods often used with social constructivism:

- semi-structured interviews (deep meanings and interpretations)

- focus groups (how meaning forms in group discussion)

- observations (how interaction creates shared norms)

- document and discourse analysis (how institutions shape “truth”)

- Data analysis often emphasizes:

- themes and patterns of meaning

- language choices and repeated narratives

- contradictions and tensions (what is contested, not settled)

Strengths of Social Constructivism

Captures complexity

- It explains why human beliefs and behaviors are shaped by:

- family and peers

- culture and tradition

- institutions and professional norms

- It avoids “one-size-fits-all” explanations when human meaning is central.

Promotes inclusivity

- It values diverse viewpoints because different social positions produce different experiences.

- It challenges assumptions that one group’s knowledge is automatically the standard.

Supports reflective practice

- Social constructivism encourages people to ask:

- “How did we come to believe this?”

- “Who benefits from this definition?”

- “What voices are missing?”

- This is useful in education, healthcare, management, and policy design.

Criticisms and Limitations of Social Constructivism

Risk of relativism

- A common critique is that if meaning is socially constructed, then “anything goes.”

- Strong constructivist research avoids this by:

- using evidence carefully

- showing how interpretations are formed

- being transparent about reasoning

- The goal is not to deny reality.

- It is to explain how meaning is produced around reality.

Limited generalizability

- Findings are often tied to a specific context or group.

- This is a limitation if a study needs broad prediction.

- It can be a strength when the goal is deep understanding.

Researcher influence

- The researcher is part of the meaning-making process.

- This can bias results if unmanaged.

- Constructivist approaches respond by emphasizing:

- reflexivity (tracking assumptions)

- transparency (clear methods and decisions)

- credibility checks (member checking, triangulation where appropriate)

Comparison With Other Theoretical Perspectives

Contrast with positivism

- Positivism assumes:

- an objective reality that can be measured

- knowledge is best produced through control and prediction

- Social constructivism assumes:

- meaning is socially shaped

- knowledge is best understood through context and interpretation

- Both can be useful.

- The choice depends on the research question.

Contrast with cognitive theories

- Cognitive theories emphasize mental processes inside the individual.

- Social constructivism emphasizes:

- interaction, language, and culture as drivers of learning

- In practice, many educators blend both:

- cognition explains internal processing

- constructivism explains how social context shapes that processing

Practical Applications of Social Constructivism Beyond Academia

Workplace learning

- Knowledge often spreads through:

- mentoring

- teamwork

- informal conversations

- “how things are done here” norms

- Social constructivism explains why onboarding works best when new staff join real communities of practice.

Healthcare and social work

- It highlights how patient meaning matters.

- How a person defines illness affects adherence, coping, and help-seeking.

- It also explains professional culture:

- what a team treats as “urgent,” “safe,” or “standard care” is partly socially shaped.

Policy and development work

- Policies succeed more when stakeholders help define the problem and the solution.

- Constructivist thinking supports:

- participatory planning

- community-led definitions of needs

- culturally responsive interventions

Using Social Constructivism as a Theoretical Framework in Research

Framing the research problem

- Social constructivism frames problems as socially produced, not purely technical.

- You position your study around:

- how meanings are formed

- how people interpret experiences

- how social context influences beliefs and actions

- Example framing:

- “This study explores how frontline nurses construct the meaning of patient safety within staffing constraints.”

Guiding research questions

- Research questions align with meaning and interaction.

- Strong question patterns include:

- “How do participants understand…?”

- “How do people construct meaning around…?”

- “How do social interactions shape…?”

- “How does context influence interpretations of…?”

Informing methodology

- Common designs:

- qualitative case study

- phenomenology (lived experience)

- ethnography (culture and practice)

- grounded theory (building theory from data)

- Data collection emphasizes:

- dialogue, narratives, and interaction

- context details (setting, roles, routines)

Shaping data analysis

- Analysis focuses on:

- themes (shared meanings)

- narratives (common storylines)

- discourse (how language shapes reality)

- social processes (how understanding forms over time)

- Findings are reported as:

- interpretations supported by participant evidence

- shaped by context, not claimed as universal law

Ensuring rigor

- Rigor in social constructivism is shown through:

- reflexivity (what you bring as a researcher)

- credibility (do participants recognize the interpretation?)

- audit trail (clear steps in analysis)

- thick description (enough context for readers to judge transferability)

Conclusion

- Social constructivism offers a practical way to understand how people build meaning in real life.

- It is powerful for topics where context, language, identity, culture, and relationships shape what people believe and do.

- In education, it supports collaboration and active learning.

- In research, it provides a strong framework for studying interpretation, experience, and social processes.

- Used well, it helps produce findings that are not only accurate within context, but also useful for improving practice and understanding human behavior.