Systems Thinking: The Practical Guide to Understanding Complexity and Creating Better Outcomes

- Systems thinking is a way of understanding reality by focusing on relationships, patterns, and interdependence.

- Instead of treating a problem as a single “thing,” systems thinking asks you to see how parts interact over time.

- When you practice systems thinking, you stop asking only “What is broken?” and start asking “What is producing this result?”

- Systems thinking is especially useful when problems are messy, recurring, or hard to solve with simple fixes.

- If a problem keeps coming back, systems thinking helps you identify the deeper structure that keeps recreating it.

- If quick solutions create new problems later, systems thinking helps you anticipate those delayed effects.

Why systems thinking matters right now

- Modern problems are increasingly interconnected.

- Business, health, education, climate, and technology are tightly linked.

- Systems thinking helps you avoid narrow decisions that look good locally but cause damage elsewhere.

- Many “failures” are actually predictable outcomes of system design.

- A system is perfectly designed to produce the results it produces.

- Systems thinking helps you redesign processes, incentives, and feedback so the results improve.

- It reduces wasted effort from treating symptoms instead of causes.

- Symptoms are the visible signals: delays, errors, burnout, complaints, churn, rework.

- Systems thinking helps you find the structural drivers underneath those symptoms.

What systems thinking is (and what it is not)

- Systems thinking is not just “thinking big.”

- It is not vague, philosophical, or only for academics.

- Systems thinking is practical: it gives you tools to map, test, and improve real-world systems.

- Systems thinking is not about blaming individuals.

- It shifts attention from “who messed up” to “what conditions made this outcome likely.”

- It supports learning and improvement rather than fear and punishment.

- Systems thinking is not the same as complicated planning.

- You do not need a huge model to start.

- Systems thinking often begins with a simple map of relationships and feedback loops.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

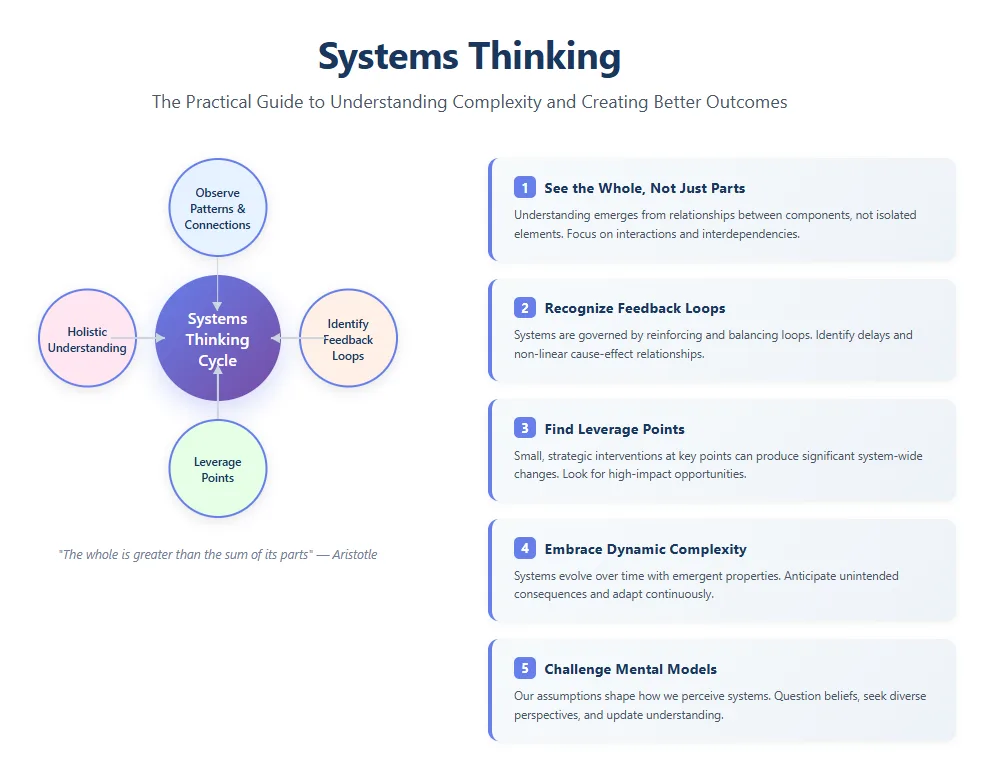

Get Started NowThe core principles of systems thinking

- Focus on relationships, not isolated parts.

- In systems thinking, the connections often matter more than the components.

- A small change in how parts interact can create a large change in outcomes.

- Look for patterns over time, not snapshots.

- A single moment can mislead you.

- Systems thinking pushes you to ask, “What has been happening over weeks, months, or years?”

- Identify feedback loops.

- Feedback loops explain why a system grows, stabilizes, or spirals.

- Systems thinking separates two loop types:

- Reinforcing loops: changes amplify themselves (growth or decline).

- Balancing loops: changes resist themselves (stabilization or goal-seeking).

- Expect delays.

- Many actions take time to show results.

- Systems thinking warns you not to overreact before the system responds.

- Watch for unintended consequences.

- A fix in one area can trigger side effects in another.

- Systems thinking trains you to ask, “What could this decision break later?”

- Find leverage points.

- Some places in a system create outsized impact.

- Systems thinking helps you stop pushing harder in low-impact areas and start nudging high-impact ones.

Key concepts you should know to practice systems thinking

- System

- A set of parts that interact to produce outcomes.

- In systems thinking, outcomes emerge from structure, not from a single cause.

- Stocks and flows

- Stocks are accumulations (inventory, trust, fatigue, savings, knowledge).

- Flows change stocks (sales, recovery, spending, learning).

- Systems thinking uses stocks and flows to explain why change can feel slow and then suddenly accelerate.

- Boundaries

- Every analysis chooses what to include and exclude.

- Systems thinking encourages flexible boundaries: start small, then expand if the system pushes effects across your boundary.

- Emergence

- System-level behavior that cannot be explained by any one part alone.

- Systems thinking highlights how “culture,” “traffic,” or “market behavior” emerges from many interactions.

- Nonlinearity

- Cause and effect are not always proportional.

- Systems thinking prepares you for tipping points, thresholds, and sudden shifts.

A simple step-by-step method for applying systems thinking

- Step 1: Define the outcome you want (and the outcome you have).

- Write the current result in plain language.

- Write the desired result with a measurable direction (increase, decrease, stabilize).

- Step 2: Describe the behavior over time.

- Sketch a quick timeline: is the problem rising, falling, cycling, or stuck?

- Systems thinking begins with trends because trends reveal system behavior.

- Step 3: List the key variables that influence the outcome.

- Include both “hard” variables (time, cost, staffing) and “soft” variables (trust, morale, perceived fairness).

- Systems thinking works best when you include human factors, not just numbers.

- Step 4: Map causal relationships.

- Use simple arrows: “A increases B,” “A decreases B.”

- Do not aim for perfection. Systems thinking maps are working drafts.

- Step 5: Find reinforcing loops and balancing loops.

- Look for circular chains where effects come back to influence the cause.

- Systems thinking becomes powerful when you can say, “This loop is driving the pattern.”

- Step 6: Identify leverage points.

- Ask: “Where can a small change reduce the harmful loops or strengthen the helpful loops?”

- Systems thinking favors policy, incentives, information flows, and constraints over motivational speeches.

- Step 7: Test changes safely.

- Use pilots, simulations, or staged rollouts.

- Systems thinking respects risk: you learn without breaking the system.

- Step 8: Measure and adapt.

- Track leading indicators, not only final outcomes.

- Systems thinking treats improvement as ongoing learning, not a one-time project.

Practical tools used in systems thinking (with easy examples)

- Causal loop diagrams

- A visual map of cause-and-effect feedback loops.

- Example:

- More workload → more stress → more mistakes → more rework → more workload.

- Systems thinking uses this to show why teams feel trapped.

- Stock-and-flow diagrams

- Useful when accumulation matters.

- Example:

- Customer support backlog (stock) grows when new tickets (inflow) exceed resolved tickets (outflow).

- Systems thinking uses this to explain why “working harder” may not reduce backlog without changing inflow or capacity.

- Iceberg model

- A way to see deeper layers:

- Events → patterns → system structures → mental models.

- Systems thinking uses it to move from reacting to redesigning.

- A way to see deeper layers:

- Leverage point analysis

- A method to prioritize interventions.

- Systems thinking helps you choose interventions that change structure rather than surface activity.

- Scenario testing

- “If we change X, what happens to Y over time?”

- Systems thinking is stronger when paired with clear hypotheses and monitoring.

Common mistakes that weaken systems thinking

- Mistake: Confusing activity with impact.

- Being busy does not mean the system is improving.

- Systems thinking asks, “What changed in the feedback loops?”

- Mistake: Treating the map as the truth.

- A map is a tool for learning, not a final answer.

- Systems thinking stays humble and updates based on evidence.

- Mistake: Ignoring delays.

- People often abandon a good change too early.

- Systems thinking encourages patience paired with measurement.

- Mistake: Fixing one point while the system adapts around it.

- Systems resist change when incentives and constraints remain the same.

- Systems thinking requires aligning rules, metrics, and behaviors.

- Mistake: Leaving out power, incentives, and information.

- Real systems are shaped by who decides, who benefits, and who knows what.

- Systems thinking must include decision rights and information flows.

Real-world examples of systems thinking in action

- Business operations

- Systems thinking reveals how short-term cost cutting can reduce quality, increase returns, overload support, and finally increase total cost.

- A systems thinking response might include improving upstream quality, redesigning workflow, and adjusting performance measures.

- Healthcare and patient outcomes

- Systems thinking shows how staffing ratios, documentation burden, and communication patterns influence errors and burnout.

- A systems thinking approach might reduce low-value tasks, improve handoffs, and strengthen learning systems.

- Education and student performance

- Systems thinking highlights how attendance, family support, sleep, mental health, classroom climate, and assessment practices interact.

- A systems thinking intervention might target early warning indicators, not only test preparation.

- Technology and product development

- Systems thinking explains why shipping faster can increase defects, which increases hotfixes, which reduces future capacity.

- A systems thinking strategy might rebalance speed and stability through automated testing, clearer definitions of done, and smarter backlog rules.

- Personal productivity

- Systems thinking helps you see burnout loops: overcommitment → poor sleep → lower focus → longer work hours → more overcommitment.

- A systems thinking fix targets the structure: limits, recovery time, and fewer hidden inflows of commitments.

How to use systems thinking as a theoretical framework in a research paper or dissertation

- Position systems thinking as your lens for explaining complex relationships.

- Systems thinking works well when your topic involves multiple interacting variables and feedback.

- It supports explanations that go beyond single-cause reasoning.

- Define the system you are studying with a clear boundary and rationale.

- State what is inside the system (actors, processes, environments).

- State what is outside the system and why.

- Systems thinking becomes academically strong when your boundary choices are transparent.

- Develop a conceptual model grounded in systems thinking.

- Present a causal loop diagram or a logic map that shows key variables and feedback loops.

- Explain how reinforcing loops and balancing loops relate to the phenomenon.

- This is where systems thinking moves from “idea” to “framework.”

- Formulate research questions that match systems thinking logic.

- Good systems thinking research questions often:

- Explore interactions (“How do factors A and B jointly influence outcome C over time?”).

- Examine feedback (“What feedback mechanisms sustain this pattern?”).

- Identify leverage (“Which structural conditions could shift outcomes most effectively?”).

- Good systems thinking research questions often:

- Translate your systems thinking model into testable propositions or themes.

- For quantitative research:

- Convert key links into hypotheses (for example, increases in workload predict increases in error rates, mediated by fatigue).

- For qualitative research:

- Convert system links into interview or coding categories (for example, incentives, information gaps, delays, adaptation behaviors).

- Systems thinking supports mixed methods well because it welcomes multiple data types.

- For quantitative research:

- Use systems thinking to guide data collection.

- Collect data across different levels, not just one.

- Example levels:

- Individual experiences

- Team workflow

- Organizational policy

- External environment

- Systems thinking helps justify why multi-level data is necessary.

- Use systems thinking to structure analysis and interpretation.

- Instead of reporting variables in isolation, interpret findings as system behavior.

- Explain how loops and delays create the observed outcomes.

- Systems thinking improves discussion chapters because it connects results into a coherent mechanism.

- Use systems thinking to design recommendations that address structure.

- Recommendations should target leverage points:

- Incentives and metrics

- Information flows and transparency

- Constraints and bottlenecks

- Rules, policies, and decision rights

- Systems thinking strengthens practical impact because it avoids shallow “train people more” solutions.

- Recommendations should target leverage points:

- Be explicit about limitations using systems thinking language.

- Acknowledge boundary limits, measurement gaps, and dynamic complexity.

- Explain which parts of the system were not captured and how that might influence conclusions.

- Systems thinking frameworks look more credible when limitations are openly discussed.

Closing takeaways

- Systems thinking helps you solve the right problem, not just the visible one.

- It reveals feedback loops, delays, and unintended consequences.

- Systems thinking improves decisions by shifting focus from blame to structure.

- You can redesign incentives, information, and constraints to get better outcomes.

- Systems thinking is both practical and research-ready.

- It can guide your research questions, your conceptual model, your analysis, and your recommendations.