Thematic statement definition

- A thematic statement is a single sentence that explains a central idea a story explores through plot, character’s choices, and consequence.

- It is a clear, universal message the author is trying to express, written as a claim a reader can agree or disagree with.

- It is not a topic word, not a question, and not a summary of action.

- It usually names a central theme (such as loyalty, trust, identity, freedom, safety, or choice) and states what the story suggests about human nature.

- It should compel the reader because it connects a specific journey to a deeper concept that can apply directly to real life.

- A strong thematic statement is specific, evidence-based (supported by events), and shaped by conflict in the setting.

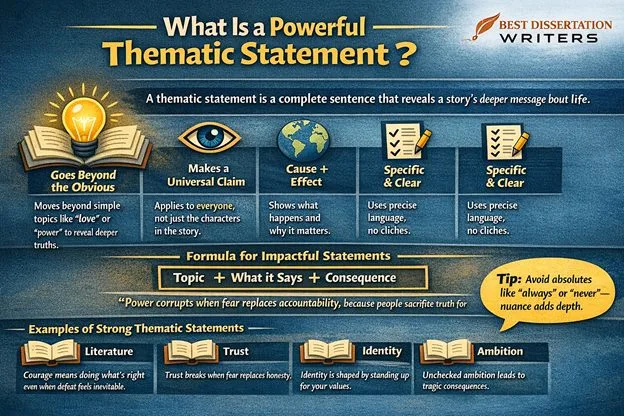

What is a thematic statement?

- Think of it as the “meaning layer” under the plot.

- Plot = what happens in the story (events, battle, decision, action, finish).

- Theme statement = what those events demonstrate about people and life, ultimately.

- It answers the hidden question: “What is the author is trying to show about this topic?”

- It is often built from three parts:

- The theme (the big concept).

- The claim (what the author suggests about that concept).

- The consequence (why it matters, or what happens when people ignore it).

- It should be one sentence because a single sentence forces clarity and removes obvious filler.

Why thematic statement matters in content and story

- For learning and teaching

- Helps a teacher guide discussion beyond “I liked the book.”

- Helps a writer plan a novel or short story with purpose.

- Helps readers identify what ideas underlie the scenes, not just what happened directly.

- For writing and revision

- Keeps content focused on a central theme, not random plot episodes.

- Prevents a story from becoming a list of events with no message the author is trying to express.

- Makes it easier to choose which scenes to keep, cut, or expand in detail.

- For analysis and literary skills

- Gives a guide for collecting evidence (scenes, dialogue, decisions) that demonstrate the theme.

- Improves how you write theme statements in essays, book reports, and class posts.

- Strengthens how you explain the author is trying to communicate something universal.

Understanding the concept of theme, topic, and thematic statement

- Theme

- The central idea about life a story explores (for example: trust, loyalty, identity, freedom).

- Usually universal and emotional, because it connects to human experience.

- Topic

- The subject area the story talks about (for example: war, family, school, money, nature).

- A topic is a category, not a message.

- Thematic statement

- The sentence that turns theme into meaning.

- It states what the story argues about the theme, based on plot and conflict.

Differences between theme vs topic

- Topic is a label; theme is an insight.

- Topic: “family”

- Theme: “family loyalty can demand sacrifice”

- Topic is what you can point to; theme is what you have to infer.

- Topic: “a boy in a new school”

- Theme: “identity strengthens when a person chooses integrity over approval”

- Topic is often concrete; theme is often abstract.

- Topic: “a battle to conquer a kingdom”

- Theme: “power gained through fear destroys trust and safety”

- Topic can be one word; theme needs explanation.

- Topic: “freedom”

- Theme: “freedom requires responsibility, or it becomes chaos”

Differences between theme statements vs plot summary

- Plot summary

- Tells what happens, in order.

- Focuses on setting, characters, events, and outcomes.

- Example: “A boy leaves home, faces a battle, and returns changed.”

- Theme statements

- Explain what those events mean.

- Focus on choice, consequence, and the central message.

- Example: “A difficult journey shapes identity when a person chooses courage over comfort.”

- A quick test

- If your sentence can be answered with “Then what?” it is probably plot.

- If your sentence can be debated in a discussion, it is probably theme.

Where character fits in a theme statement

- Character is the engine that turns theme into story.

- Theme becomes visible through what a character does under pressure.

- Conflict forces decision, and decision reveals values.

- Character-based meaning

- A character’s fear, loyalty, trust, or desire for freedom creates the emotional core.

- The theme emerges from consequence: what the character gains, loses, or learns.

- Use character without naming the character

- Instead of naming a person, describe the type of person:

- “A leader,” “a child,” “a friend,” “a newcomer,” “a parent,” “a writer.”

- Instead of naming a person, describe the type of person:

- Tie character to evidence

- Choose moments where the character’s choice changes the plot and demonstrates the central theme.

Need help writing a strong thematic statement?

Get clear, step-by-step support to turn a theme topic into a precise, one-sentence claim (with examples, feedback, and revisions) from Best Dissertation Writers .

- Theme vs topic explained in simple terms

- A ready-to-use formula: topic + what it says + consequence

- Polished thematic statement examples for your story or novel

- Quick edits to improve clarity, specificity, and depth

Types of thematic statement

- Not every story needs the same type.

- Different types help you match the sentence to what the author is trying to do.

Universal theme statement

- Focuses on people in general, not one specific character.

- Works best when the theme is broad and applies across settings.

- Signals words you may use:

- “People,” “we,” “humans,” “society,” “individuals,” “anyone.”

- Example structure

- “When people __________, they often __________, because __________.”

- Example

- “When people value loyalty over truth, they can protect relationships short-term but destroy trust long-term.”

Character-based thematic statement

- Focuses on how a character’s inner change reveals meaning.

- Works best for coming-of-age stories, identity arcs, and moral conflicts.

- Example structure

- “A person discovers __________ when they choose __________ over __________.”

- Example

- “A person strengthens identity when they choose self-respect over approval, even when the consequence is loneliness.”

Conflict-based thematic statement

- Focuses on how conflict exposes values and creates consequence.

- Works best for high-stakes plot, external threats, and ethical dilemmas.

- Example structure

- “In the face of __________, __________ leads to __________.”

- Example

- “In the face of injustice, silence enables harm, while action protects safety and freedom.”

How to write thematic statements

- Use this as a practical guide you can apply to any book, novel, or short story.

- Aim for one sentence, clear logic, and a claim supported by evidence from the plot.

Step 1: Choose a theme topic

- Identify the topic first, then move deeper.

- Ask: “What keeps repeating in the story?”

- Look for repeated choices, arguments, symbols, or consequences.

- Common theme topics to start with

- Loyalty, trust, identity, freedom, safety, power, love, fear, justice, belonging.

- Fast prompts to find the theme topic

- What does the character want most?

- What does the character fear losing?

- What conflict forces the hardest decision?

- What lesson seems to underlie the ending?

Step 2: Turn the topic into a clear sentence

- Convert a single word topic into a claim.

- Topic: “trust”

- Sentence draft: “Trust is fragile.”

- Improve clarity by specifying conditions.

- “Trust breaks when people hide the truth to avoid short-term conflict.”

- Keep it one sentence

- One sentence prevents you from stacking multiple themes into one unclear paragraph.

- Avoid obvious statements

- If it sounds like a generic poster line, it may be too vague.

Step 3: Add a universal insight that compels

- Make it universal

- Remove names, unique places, or one-time events.

- Keep the insight applicable to real life.

- Make it compelling

- Show stakes: what is gained or lost.

- Connect to emotion: fear, love, pride, shame, hope.

- Useful “compel” tools

- Add consequence: “which leads to…”

- Add contrast: “but…”

- Add cause-and-effect: “because…”

- Example upgrade

- Basic: “Freedom matters.”

- Compelling: “Freedom becomes meaningful only when a person accepts responsibility for the consequence of their choice.”

Step 4: Check the statement for clarity and specificity

- Clarity checks

- Can a reader understand it without reading the plot summary?

- Does every word earn its place in the sentence?

- Is the statement directly connected to what happens in the story?

- Specificity checks

- Does it say how or why, not just what?

- Does it avoid cliche phrases like “love conquers all” unless the story demonstrates it in a fresh way?

- Evidence checks

- Can you point to at least three moments that demonstrate the claim?

- Do those moments show conflict, decision, and consequence?

Thematic statement examples

Example 1: Theme statement examples for common themes

- Loyalty

- “Loyalty becomes harmful when it demands silence about wrongdoing, because protection without honesty destroys trust.”

- Trust

- “Trust is built through consistent truth-telling, and it collapses when fear turns relationships into performance.”

- Identity

- “Identity strengthens when a person stops chasing approval and chooses values, even when the cost is rejection.”

- Freedom

- “Freedom without responsibility becomes selfishness, but freedom with accountability creates safety for others.”

- Choice

- “A single choice can shape a life more than talent, because decision reveals character under pressure.”

- Nature

- “When people treat nature as a tool instead of a living system, they inherit consequences they cannot control.”

Theme statement examples for common themes

A theme statement is the sentence that explains what the story suggests about a theme. The highlighted line below is the thematic statement.

Theme: Trust

Thematic statement: Trust breaks when fear replaces honesty, because relationships cannot survive constant suspicion.

Example (in a story): A friend hides the truth to avoid conflict, but the lie grows and ruins the friendship.

Theme: Loyalty

Thematic statement: Loyalty becomes harmful when it demands silence about wrongdoing, because it destroys trust over time.

Example (in a story): A character protects a friend’s mistake, but the cover-up hurts everyone involved.

Theme: Identity

Thematic statement: Identity strengthens when a person chooses values over approval, even when the cost is rejection.

Example (in a story): A student stops performing for others and makes a difficult decision that reflects self-respect.

Tip: The thematic statement is the sentence that makes a universal claim (not a plot summary).

Example 2: Thematic statement examples by story type

- Short story

- “In a short story, small actions reveal big truths: a single moment of honesty can restore trust after long avoidance.”

- Coming-of-age story

- “Growing up means learning that identity is not given by others, but chosen through everyday courage.”

- Mystery story

- “The search for truth exposes how lies multiply conflict, because each hidden detail creates new consequence.”

- Romance story

- “Love fails when it becomes control, because possession cannot coexist with freedom.”

- Adventure story

- “A journey tests character, and the hardest battle is often the decision to keep going when doubt is louder than hope.”

- War or battle story

- “Violence may help someone conquer a goal, but it often leaves emotional damage that reshapes identity long after the fight ends.”

- Dystopian novel

- “When a society trades freedom for safety without limits, it creates a system where fear becomes the central tool of control.”

Thematic statement examples by story type

Below, each example includes the story type, then a highlighted line showing the thematic statement. A short story idea is included to show how it could appear in a plot.

Story type: Coming-of-age

Thematic statement: Growing up means choosing values over approval, because identity is built through hard decisions.

Example plot idea: A student risks losing friends by refusing to participate in bullying, and discovers self-respect.

Story type: Mystery

Thematic statement: Truth is uncovered when people face discomfort, because hiding facts allows conflict and harm to grow.

Example plot idea: A detective finds that each lie protects someone briefly, but creates bigger consequences later.

Story type: Romance

Thematic statement: Love fails when it becomes control, because respect and freedom are the foundation of trust.

Example plot idea: One partner tries to “protect” the other by limiting choices, and the relationship breaks down.

Story type: Adventure

Thematic statement: A journey reveals character, because courage is proven by the choices people make under pressure.

Example plot idea: A team must choose between easy success and doing what is right, even when it risks failure.

Tip: If you change the plot, the thematic statement should still remain true for the story type.

Example 3: Statement examples for different characters and conflicts

- A boy facing peer pressure (identity conflict)

- “A boy learns that identity is stronger than popularity when he chooses integrity and accepts the consequence of standing alone.”

- A leader facing betrayal (trust conflict)

- “Trust breaks when power becomes more important than people, because leadership without empathy turns loyalty into fear.”

- A friend group after a lie (loyalty conflict)

- “Loyalty is proven through truth, not secrecy, because protecting a lie harms the relationship more than admitting it.”

- A family in crisis (choice conflict)

- “In crisis, the choices people make reveal their values, and those values shape the future more than the crisis itself.”

- A character vs setting (nature conflict)

- “When survival depends on nature, arrogance collapses, and humility becomes the difference between danger and safety.”

Statement examples for different characters and conflicts

Each section below lists a character type and the conflict, then highlights the thematic statement. A brief plot hook shows how the idea could appear in a story.

Character: A boy new to school • Conflict: identity vs approval

Thematic statement: Identity becomes stronger when a person chooses integrity over popularity, even when rejection feels unbearable.

Plot hook: He refuses to join a cruel prank, loses “friends,” and discovers self-respect.

Character: A leader • Conflict: trust vs power

Thematic statement: Trust collapses when power becomes more important than people, because fear cannot create real loyalty.

Plot hook: The leader demands obedience, but betrayal grows until the group breaks apart.

Character: Two best friends • Conflict: loyalty vs honesty

Thematic statement: Loyalty is proven through truth, not secrecy, because protecting a lie harms relationships more than admitting it.

Plot hook: One friend covers up a mistake “to help,” but the hidden truth causes a bigger fallout later.

Character: A parent • Conflict: safety vs freedom

Thematic statement: Safety becomes fragile when fear limits freedom, because control cannot protect people from every consequence.

Plot hook: A parent restricts every choice, and the child becomes unprepared for real-world risk.

Character: A rival pair • Conflict: ambition vs consequence

Thematic statement: Ambition turns destructive when winning matters more than integrity, because success gained by harm carries lasting consequences.

Plot hook: One rival cheats to conquer the competition, but the victory costs reputation, trust, and peace.

Tip: A strong thematic statement links character choice to conflict and consequence, without summarizing every plot event.

How to revise and strengthen a theme statement

- Revision is where a good sentence becomes powerful.

- Use these tips to remove obvious phrasing, increase clarity, and tighten logic.

Tip 1: Make the sentence more precise

- Replace vague words with specific meaning.

- Vague: “bad,” “good,” “things,” “stuff.”

- Precise: “betrayal,” “risk,” “responsibility,” “isolation,” “accountability.”

- Add conditions.

- “Trust matters” → “Trust matters most when conflict makes honesty costly.”

- Limit to one central theme

- If your sentence includes three big ideas, you probably have three theme statements.

Tip 2: Avoid vague or moralizing statements

- Avoid preaching tone that sounds like a teacher scolding a class.

- Avoid “always/never” unless the story truly supports it.

- Avoid cliche morals that do not match the story’s detail.

- If the plot shows mixed outcomes, your statement should reflect complexity.

- Aim for an insight, not a lecture.

- “People should be nice” is obvious.

- “Kindness becomes courage when it risks social punishment” is more literary.

Tip 3: Test the statement against the story

- Evidence test

- List 3–5 moments from the plot that support the claim.

- Include at least one turning-point decision.

- Counterexample test

- Ask: “Does any scene contradict my claim?”

- If yes, refine the sentence so it matches what the author is trying to show.

- Reader test

- Ask: “Would a reader who disagrees still find this debatable?”

- If yes, your statement has discussion value.

Tip 4: Make sure all the thematic statement checklists are met

- Checklist for a strong thematic statement

- One sentence, not a paragraph.

- States a universal claim, not a topic.

- Connects theme to conflict, choice, and consequence.

- Avoids plot summary and names.

- Uses clear cause-and-effect language.

- Can be supported by evidence from the story.

- Feels compelling, not obvious.

- Quick “tighten” moves

- Remove extra adjectives.

- Replace “is about” with a direct claim.

- Add “because” or “which leads to” when logic is missing.

Common mistakes to avoid when writing a thematic statement

- Mistake: Writing a topic instead of a statement

- Topic: “freedom”

- Better: “Freedom becomes dangerous when it ignores responsibility.”

- Mistake: Writing plot summary

- Plot: “The character leaves home and returns.”

- Theme: “A journey changes identity when a person confronts fear instead of running from it.”

- Mistake: Making it too moralizing

- Moralizing: “People should always tell the truth.”

- Stronger: “Truth can threaten comfort, but hiding it creates conflict that grows over time.”

- Mistake: Using a cliche without proof

- Cliche: “Love conquers all.”

- Stronger: “Love can heal conflict, but only when it respects freedom and refuses control.”

- Mistake: Being too broad or too obvious

- Too broad: “Life is hard.”

- Better: “When people avoid hard decisions, they often create consequences that are harder than the truth.”

- Mistake: Ignoring character’s role

- If the character’s decisions do not shape the meaning, your theme will feel disconnected.

- Mistake: Forgetting the author’s purpose

- Keep returning to: “What is the author is trying to reveal through this conflict?”

- Track the message the author is trying to express, not just what happens directly.

Frequently asked questions about thematic statements

Can a story have more than one theme statement?

- Yes, many stories explore multiple themes, especially a novel with several characters and subplots.

- A practical approach

- Choose one central theme statement for the whole book.

- Add 1–2 secondary theme statements for major character arcs or conflicts.

- How to know which one is central

- The central one is supported by the most evidence.

- It shapes the ending and the character’s final decision.

- It is the idea that underlies the biggest consequences.

How long should a thematic statement sentence be?

- Most strong options fit in 15–30 words.

- Short is good, but not at the cost of clarity.

- Too short: “Trust matters.”

- Better: “Trust breaks when fear replaces honesty, because relationships cannot survive constant suspicion.”

- If it becomes too long

- You may be trying to fit more than one theme into a single sentence.

- Split and choose the strongest claim.

How many thematic statement examples should I include?

- For a blog post or guide, 10–20 statement examples is usually enough to support learning.

- A smart mix includes

- Common themes (trust, loyalty, identity, freedom).

- Different story types (short story, novel).

- Different conflicts (internal, interpersonal, society vs individual, character vs nature).

- Quality matters more than quantity

- Each example should demonstrate clear logic, show consequence, and feel connected to a believable plot.

Quick wrap-up

- Identify the topic, then explore what it means in the story.

- Focus on character’s choice under conflict and the consequence that follows.

- Write one clear sentence that states a universal claim.

- Support it with evidence from the plot and revise until it feels precise, compelling, and directly tied to the central theme.