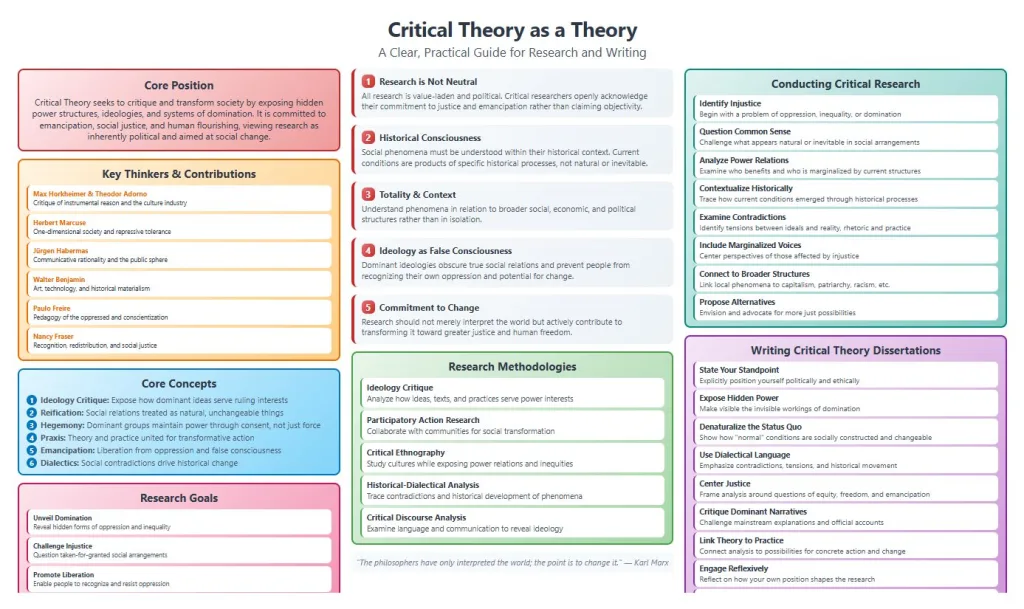

Critical theory: a clear, practical guide for research and writing

- Critical theory is a way of thinking that asks one main question: who benefits from the way society is organized, and who pays the costs.

- Critical theory treats social “common sense” as something that was built over time, not something that is naturally true.

- It focuses on power, inequality, and the everyday systems that shape people’s lives.

- It also focuses on change, not just description. It often asks what could be different, and how.

- In academic work, critical theory is used to analyze institutions, policies, language, media, workplaces, education, health systems, and technology.

What is critical theory?

- Critical theory is a theory that studies how power works in social life.

- It looks at who has authority and control, and how that control is maintained.

- It asks how rules, norms, and traditions shape what people think is “normal.”

- Critical theory argues that society is not neutral.

- Many systems are presented as objective, fair, or merit-based.

- Critical theory checks whether those claims hold up for different groups.

- Critical theory is not only about “ideas.”

- It connects ideas to real conditions, like wages, housing, policing, access to health care, or school discipline.

- It asks how these conditions shape opportunity and life outcomes.

- Critical theory often uses critique as a tool.

- Critique means carefully questioning assumptions and exposing hidden power relations.

- It does not mean criticizing for the sake of negativity. It means clarifying what is happening and why.

Where critical theory comes from

- Critical theory is strongly linked to twentieth-century European social philosophy.

- Early work is often associated with the Frankfurt School.

- Those scholars tried to explain why modern societies can produce both progress and oppression at the same time.

- Critical theory developed as a response to limits of “value-neutral” social science.

- Some research traditions aimed to describe society like a machine.

- Critical theory argued that this can hide injustice by treating it as “just how things are.”

- Critical theory also grew through later traditions.

- Feminist theory, postcolonial theory, critical race theory, disability studies, and queer theory all shaped the broader critical tradition.

- These approaches pushed scholarship to take lived experience and structural inequality seriously.

The central goal of critical theory

- Critical theory aims to reveal how domination and inequality become normal.

- It focuses on the gap between what society claims to value and what society actually does.

- For example, a system may claim to value “equal opportunity,” while practices produce unequal outcomes.

- Critical theory aims to support human freedom and dignity.

- It does not treat people as passive.

- It focuses on agency, resistance, and the possibility of transformation.

- Critical theory is often described as both explanatory and emancipatory.

- Explanatory: it tries to explain how power operates.

- Emancipatory: it aims to reduce harm and expand justice.

Core assumptions you should understand

- Power is built into structures, not only individual actions.

- Discrimination can exist even without “bad intentions.”

- Policies, routines, and institutional habits can still produce unfairness.

- Knowledge is shaped by context.

- What counts as “truth” can be influenced by who has status and voice.

- Some groups are treated as more credible than others.

- Language matters because it can shape reality.

- Words influence how problems are defined and what solutions seem “reasonable.”

- Labels can stigmatize groups or erase their experiences.

- Inequality is reproduced through everyday practices.

- Hiring criteria, grading systems, clinical pathways, surveillance tools, and workplace norms can all reproduce hierarchy.

- These processes often look neutral on the surface.

- Social change is possible, but not automatic.

- Critical theory studies both domination and resistance.

- It asks what conditions make change more likely.

Key concepts explained in simple terms

- Ideology

- Ideology is a set of beliefs that makes unequal arrangements feel natural or inevitable.

- It can show up in slogans like “anyone can succeed if they work hard,” even when barriers are unequal.

- Critical theory examines which beliefs protect the status quo and why.

- Hegemony

- Hegemony is power that works through consent, not just force.

- People may accept unfair systems because they seem normal, moral, or “just the way it is.”

- Critical theory often asks how hegemony is built through schools, media, and culture.

- Domination and oppression

- Domination refers to patterns where some groups control resources, rules, and recognition.

- Oppression includes the harms that follow, such as exclusion, silencing, exploitation, or marginalization.

- Critical theory focuses on these patterns across institutions, not only interpersonal events.

- Social reproduction

- This means inequality can repeat itself across generations.

- For example, unequal schooling can lead to unequal jobs, which leads to unequal housing, which shapes future schooling.

- Critical theory traces these cycles and identifies leverage points for change.

- Intersectionality

- People do not experience inequality in only one way.

- Race, gender, social class, disability, migration status, and sexuality can interact.

- Critical theory often uses intersectionality to avoid oversimplified explanations.

- Emancipation

- Emancipation means reducing domination and expanding human capacity to live well.

- In research, this can mean producing knowledge that helps improve policies and practices.

- Critical theory treats emancipation as a serious research aim, not just a personal opinion.

What critical theory is not

- Critical theory is not the same as being politically “for” or “against” a party.

- It is a scholarly approach with concepts, claims, and methods.

- It can be applied carefully, with evidence.

- Critical theory is not only about criticizing individuals.

- It focuses on systems and structures.

- It asks how institutions shape behavior and outcomes.

- Critical theory is not automatically anti-science.

- It often critiques narrow ideas of objectivity.

- But it still values rigorous reasoning, transparency, and evidence.

How critical theory differs from other theories

- Compared with positivist approaches

- Positivist approaches often focus on measurement and prediction.

- Critical theory focuses on meaning, power, and the social conditions behind the numbers.

- It asks why a pattern exists and who is affected by it.

- Compared with interpretivist approaches

- Interpretivism often centers lived meaning and subjective experience.

- Critical theory also values experience, but it ties experience to structural forces. Use both, but do not stop at description.

- Compared with functionalist approaches

- Functionalism often sees institutions as serving social stability.

- Critical theory asks whether “stability” is being bought through injustice.

Typical research questions shaped by critical theory

- Who has decision-making power in this setting, and who does not?

- What rules or norms appear neutral but create unequal outcomes?

- How is “success” defined, and whose values are embedded in that definition?

- Which groups are silenced or excluded from participation, and how?

- How do people resist, cope, or negotiate power in daily life?

- What reforms are proposed, and do they reduce inequality or simply repackage it?

Methods that fit critical theory

- Critical theory can work with qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, but the logic matters.

- The methods should match the aim: revealing power relations and their effects.

- The study should also make clear what “justice” or “equity” means in your context.

- Common qualitative methods

- Interviews and focus groups to capture lived experience and meaning.

- Ethnography to observe power in everyday practices.

- Document analysis to examine policy, institutional language, and official narratives.

- Critical discourse analysis to show how language produces categories, blame, or legitimacy.

- Common quantitative and mixed-method options

- Inequality mapping (for example, disparities in outcomes by group).

- Statistical modeling with attention to structural variables and confounders.

- Surveys combined with qualitative interviews to connect patterns with lived realities.

- Program evaluation focused on equity outcomes, not only overall averages.

Strengths of critical theory in academic writing

- It helps you go deeper than surface explanations.

- It pushes you to ask “what structures produce this problem.”

- It reduces the risk of blaming individuals for structural harm.

- It improves policy and practice relevance.

- Many real-world problems are shaped by institutions.

- Critical theory gives you tools to analyze those institutions clearly.

- It supports ethical research reasoning.

- It highlights voice, participation, and the consequences of knowledge production.

- It encourages you to consider who your research helps.

Need expert dissertation writing support?

Get structured guidance, clear academic writing, and on-time delivery with Best Dissertation Writers .

Get Started NowCommon critiques and how to handle them

- Critique: “It is biased or political.”

- Response: all theories have assumptions. State yours openly.

- Use evidence carefully. Show how your claims follow from data and analysis.

- Critique: “It is too abstract.”

- Response: anchor concepts in concrete examples from your setting.

- Define each key term in your own words and apply it consistently.

- Critique: “It only criticizes and offers no solutions.”

- Response: build an explicit implications section.

- Provide feasible recommendations linked to findings.

- Critique: “It overemphasizes structure and ignores agency.”

- Response: include how people resist, adapt, and create change.

- Show the interaction between structure and individual action.

Where critical theory is commonly applied

- Education

- Analyzing curriculum, school discipline, tracking, and “achievement gaps.”

- Studying how schools can reproduce social class inequality.

- Health and nursing

- Examining access to care, treatment bias, and institutional policies.

- Studying social determinants of health and structural barriers.

- Media and culture

- Analyzing representation, stereotypes, and narrative power.

- Studying how platforms shape attention, identity, and public debate.

- Organizations and workplaces

- Examining organizational hierarchy, inclusion, pay equity, and labor conditions.

- Studying how “professionalism” norms can exclude certain groups.

- Technology and data systems

- Examining algorithmic bias, surveillance, and the politics of “efficiency.”

- Studying how data categories shape what institutions can see and ignore.

Using critical theory as a theoretical framework in a research paper or dissertation

- A theoretical framework is the lens that shapes what you study, how you define concepts, and how you interpret results.

- Critical theory works well as a framework when your topic involves power, inequality, injustice, or institutional harm.

- It can also work when your topic is about “neutral” systems that may produce unequal effects, like policies, grading criteria, or digital tools.

Step 1: State why critical theory is the right lens

- Explain what problem you are studying and why a power-focused lens is needed.

- State what “power” means in your specific topic.

- Power can mean control of resources, decision-making authority, cultural legitimacy, or voice in participation.

- Use critical theory to justify moving beyond individual-level explanations.

Step 2: Define your key concepts as you will use them

- Pick a small set of concepts from critical theory and define them clearly.

- Example concept sets that often work well

- Power, ideology, and hegemony (for institutional normalization)

- Oppression, marginalization, and intersectionality (for group-based inequality)

- Discourse and legitimacy (for language and policy analysis)

- Keep definitions practical. Avoid long philosophical detours unless your dissertation requires it.

Step 3: Turn the theory into research questions

- A strong critical framework produces questions that expose mechanisms.

- Good patterns for critical questions

- What institutional practices produce unequal outcomes in this setting?

- How do policies define the “problem,” and who is blamed or protected?

- How do participants experience, interpret, and resist these structures?

- Make sure your questions can be answered with your data.

Step 4: Align methods with critical theory

- Show how your method will reveal power relations.

- Examples of strong alignment

- Policy document analysis to identify how institutions construct “deserving” vs “undeserving” groups.

- Interviews with those most affected to center lived experience and hidden costs.

- Observations in institutional spaces to capture routine, taken-for-granted practices.

- Mixed methods that connect disparity patterns with explanatory narratives.

Step 5: Build an analysis plan that uses the framework, not just mentions it

- Many students “name-drop” theory and then do not use it. Avoid that.

- Create an analysis structure that explicitly applies concepts from critical theory.

- Code qualitative data for power dynamics, exclusion, voice, legitimacy, and resistance.

- In document analysis, track how language assigns responsibility and authority.

- In quantitative analysis, interpret disparities as signals of structural conditions, not “group deficits.”

Step 6: Show rigor and reflexivity

- Critical research expects you to be transparent about your position.

- Include reflexivity in your dissertation methods chapter

- Your relationship to the topic and participants

- How you handled power dynamics during data collection

- How you protected participants from harm

- How you checked your interpretations (for example, member checking, peer debriefing, audit trail)

Step 7: Write findings and discussion in a theory-driven way

- In findings, show what is happening and provide evidence.

- In discussion, explain what it means through the lens of critical theory.

- Connect micro-level experiences to macro-level structures.

- Show how policies or norms become real consequences.

- Identify mechanisms, not only themes.

Step 8: End with implications that match the framework

- A critical dissertation should not end with vague advice.

- Build recommendations linked to your analysis

- Policy changes (for example, revise criteria that create exclusion)

- Practice changes (for example, training, accountability, redesign of workflows)

- Participation changes (for example, increase stakeholder voice in decision-making)

- Explain what success would look like and how it could be evaluated.

A simple framework template you can copy into your chapter

- Theoretical lens

- Critical theory is used to examine how power relations and institutional practices shape the problem under study.

- Key concepts

- Define 3–5 concepts you will apply consistently (for example, hegemony, ideology, marginalization, intersectionality).

- Analytical focus

- Identify what you will look for in data (for example, rules that appear neutral but create unequal outcomes; language that legitimizes authority; forms of resistance).

- Expected contribution

- Explain how your study will reveal mechanisms and support equitable change.

Common mistakes students make with critical theory

- Using critical theory only in the introduction

- Fix: bring it into your methods, analysis, and discussion sections.

- Being too broad

- Fix: choose a narrow set of concepts and apply them repeatedly and clearly.

- Replacing evidence with slogans

- Fix: treat every claim as something you must support with data or credible sources.

- Treating participants as only victims

- Fix: include agency, coping, and resistance. Human lives are complex.

- Offering unrealistic solutions

- Fix: propose changes that match institutional constraints and stakeholder realities.

Practical writing tips to keep the blog-level clarity in academic work

- Define terms in one or two sentences before you use them.

- Use short paragraphs and clear headings.

- In every chapter, add one “theory link” sentence that explicitly shows how critical theory shaped that section.

- When you present a finding, follow it with a “why this matters” sentence tied to power and structure.

- Keep your tone firm but fair. Aim for clarity, not outrage.

Key Takeaway

- Critical theory is a powerful way to study society because it treats inequality as something built into systems, not only individual behavior.

- It helps you ask deeper questions about institutions, rules, norms, and language.

- It also helps you write research that matters in practice, because it links evidence to change.

- When used carefully, critical theory becomes more than a topic. It becomes a usable framework that guides your questions, methods, analysis, and recommendations.